second part of outline, through year 1300.

Part One Part Three

Note: The early part of this page has some dense sections, but this will bring light to the background for the rest of the outline.

Page Index

A.D. 1093: First Occupation of Wales

Following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, William the Conqueror begins making invasion plans for Wales. This is accomplished under his son William II in 1093. This first invasion, however, was rolled back by a successful revolt by the Welsh in 1094, leaving England only in control of the southern region, but including the region of Brecknock and Monmouth where the Olchon baptist church was later located.1“Walter Brute,” Encyclopaedia Cambrensis, Vol. 10, p. 480.2Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club Herefordshire, Vol. 44 (1898), pp. 260-261.3Y Ffydd Ddi-Fyiant 3rd Ed., p. 194. The later King Henry II, who ruled from France, would continue these efforts but he suffered defeats. Wales maintained its separation until the end of the reign of its ruler Llywelyn ap Gruffydd in 1282. His brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd was executed by Edward I on October 3, 1283.4“Wales, The English Conquest,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th ed. (1929), Vol. 23, p. 296. The title Prince of Wales then entered its current usage.

Despite the relative isolation of Wales during this intervening time, outside contact between nobility was still maintained; it is noted that the last regions in Wales synchronized their calendars to the Catholic calendar by 768.5Sir John Edward Lloyd, A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, Vol. 1, p. 203.

No fewer than sixteen different colleges6See: “Asser,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 2, pp. 528-529.7“Asser (d. 909?),” Dictionary of the National Biography (1885-1900), Vol. 2, p. 198. were observed and recorded in Wales at various times throughout the pre-conquest period. These structures dedicated to religious study were not to be confused with ordinary churches.8Sir John Edward Lloyd, A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, Vol. 1, pp. 205-206.9Territory in Wales was never parceled into dioceses, nor were there metropolitan sees (or seats of bishoprics), see ibid. p. 157. In this culture, a particular form of monasticism existed, tied to training in scribe work, languages, translations and copyists. While these might be called monasteries, we have noted instead that with regard to similar structures that also existed in early Scotland and Ireland: “it has been justly observed, that they may more properly be viewed as colleges, in which the various branches of useful learning were taught, than monasteries.”10William McGavin, in his Introduction to Knox’s History of the Reformation of religion in Scotland, p. xiii.11Full quote: “Although it appears that they observed a certain institute, yet, in the accounts given of them, we cannot overlook this remarkable distinction between them and those societies which are properly called monastic, that they were not associated expressly for the purpose of observing this rule. They might deem certain regulations necessary for the preservation of order: but their great design was, by communicating instruction, to train up others for the work of the ministry. Hence it has been justly observed, that they may more properly be viewed as colleges, in which the various branches of useful learning were taught, than monasteries. These societies, therefore, were in fact the seminaries of the church, both in North Britain and Ireland. As the presbyters ministered in holy things to those in their vicinity, they were still training up others, and sending forth missionaries, whenever they had a call, or any prospects of success.” It is reasonable to extend McGavin’s conclusion to the same colleges in Wales in the same era, lasting until the conquests of 1093-1283. There is less specific information about the churches themselves. Manuscript transcription was done at the colleges, while the church buildings that these people used (the Welsh or Britons) were traditionally of wood.12As it was said, “Ecclesiam de lapide, insolito Brettonibus more.”

Bede, Eccl. Hist., lib. iii, ch. 4. Remains of stone buildings, meanwhile, are those of the Anglo-Saxon, and later Norman and English churches.

The evidence of a preserved line of manuscripts during this time, the Anglo-Saxon translation of the four Gospels, has lasted until today.13The Wessex Gospels This translation lines up with the received text of the New Testament, and not the Latin Vulgate— and could have been possessed in the original tongue then subsequently translated by native speakers into a common dialect of Old English, namely the “Wessex” dialect.14Translated in approximately A.D. 990, as mentioned in the previous article. This seems to coincide closely in space and time with the college in Llantwit Major (see A.D. 395), having been ransacked by a Viking raid in 987.15The continuation of at least one received line of scripture is important for the following reasons: “Many of the converts and churches in different parts of the world, in the first century, must have been as illiterate as the Scots were in the fourth, yet we do not find that they set one class of ministers over the rest. Those indeed who enjoyed the ministry of apostles and evangelists had the advantage of their superintendence. When they were all become extinct, their writings were left to supply their place; and they are perfectly sufficient for the purpose, —able to make the man of God perfect, thoroughly furnished for every good work, which implies being perfectly qualified for the ministry of the gospel...” (cont’d in next footnote)16“…The apostles never contemplated such a state of things in any church, as would make it lawful to depart from the order and government which they appointed, or to have recourse to human expedients on any immergency whatever. The proper measures for supplying what was wanting, would have been to multiply copies of the scriptures, to have the people generally taught to read; that at least every church should have a Bible, and some able to read it distinctly. By such means, with prayer and spiritual conference, our Christian ancestors might have had all their wants supplied.”

in: William McGavin’s Introduction to Knox’s History of the Reformation of religion in Scotland, p. viii.

A.D. 1103: The Investiture Controversy

Sharing of power and authority, between Kings and state-Bishops, became a very great controversy around this time. This dispute made its way to England in a major way around the year 1103. Many ceremonial rights in the state-appointed churches were put into question at this time. Further, deciding what temporal authority held the right of selecting (or of merely confirming) the nominations of state-bishops, the order of priority in cases of disagreement, and the ownership of symbolic objects that represented these supposed rights were greatly disputed.17“Investiture,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th ed. (1929), Vol. 12, p. 563. However, this entire controversy admittedly amounted to a political exercise, as it was unrelated to any doctrinal matters.18“Gregory VII,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th ed. (1929), Vol. 10, p. 870.

By 1103 there was already an existing dispute between the (Holy Roman) Emperor, Henry IV, who maintained one side of the dispute, and the sitting Bishop of Rome on the other side. This latter office, since 756, had been successively instated by the Emperors. The early popes had been created by the Frankish kings, this title merely existing as a continuation of Byzantine traditions. These popes, being subjects, had very little political power.19“Italy,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 12, pp. 35-36.20Gieseler, A Text-book of Church History (1857 ed.) translated by Davidson, Winstanley, Vol. II, pp. 34-42. In 1059, they created an electoral college, no longer content to remain under the power of a weaker sovereign.21“Nicholas II,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th ed. (1929), Vol. 16, p. 416. This was around the time that the term Pope began to be used only to refer to bishop of Rome in particular. No one else in the West took the Latinised title for “Father” past this date in the 11th century.22Dictatus Papae, article 11. (A.D. 1075)23The Archbishop of Canterbury still maintained for himself the title “Papa alterius orbis” however; see article, “Archbishop,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 2, p. 301. Also around this time, strife arose regarding rights claimed by the popes placing themselves over the German emperors.

The controversy spread to England when the archbishop was told not to return to England in 1103, due to his similar arguments against King Henry I of England having predominance over him.24“Anselm, archbishop of Canterbury,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 2, p. 170. The archbishop’s hand was weakened in this second dispute by the papal need for Henry I of England against the German Henry IV. This was because the Roman pope was wary of supporting the English archbishop, as long as the pope needed the English king as a threat against the German emperor. Further weakening the archbishop’s position was the existence of yet a third dispute, the Canterbury-York dispute, where the archbishop of York, another archbishop, fought for privileges over Canterbury. The English Henry relied on the archbishop of York to perform ceremonial rites while the archbishop of Canterbury was alienated.25“Roger (d. 1181), Archbishop of York,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th ed. (1929), Vol 19, p. 381. So, this second dispute strengthened the York side of the third dispute. The Pope was wary of influencing this third dispute in a way that might alienate either party, whose help might be useful at some future time in some other political dispute, such as his own dispute at present with the Emperor.

Around this time, King Henry I of England had his faction of the state church pen the strongly pro-royalist Tractatus Eboracenses.26MS. 415: The Norman Anonymous. This tractate dealt with perceived standards of time of the king’s preeminence in handling all state matters in the church of England, which would include over the whole institution of state church. This tract exists as sort of a final rebuke against any concept of “outside” interference in what are seen by it as “internal” state affairs, including the state-related matters in which the Roman state church (or its potential allies in the offices of the two Archbishops of Canterbury and York), now began ambitiously to claim its own rights. The Tractatus Eboracenses, drafted at such an early date, stands in contrast to all later claims of papal or other foreign precedence. We see from this unusual diplomatic posture by the King of England that attempted interference against the King of England would only draw the two states of Rome and England into conflict.27See: Letter of King Henry I to Paschal– in which the King Henry I threatened that (pope) Paschal ought, “using with yourself a better deliberation in this matter, let your gentleness so moderate itself,” or else the king would be “forced to withdraw his obedience” (a vestra me cogatis recedere obedientia), if the pope did not do so- noting that his nobles and the great people of England, “would not suffer it,” were he to do otherwise than what he writes.

From: Epist. Henrici ad Paschalem P. ann. 1103, in J. Bromptoni (c. 1326) chron. in Rymer foedera, etc. Regum Angliae ad h. a.

The nature of these disputes is typified in the feud in 1163 that occurred between Archbishops Roger de Pont L’Évêque and Thomas Becket as part of the Canterbury-York dispute. They argued for three entire days over who should have the more honorable seat placement at the council.28“Roger of Pont L’Evêque (d. 1181),” Dictionary of the National Biography (1885-1900), Vol. 49, p. 109. Finally, in 1352, during the plague, it was decided that the archbishop of York should be “Primate of England,” while the archbishop of Canterbury should be “Primate of all England.”

With regard to the second dispute, the kings, at least in England, always had the upper hand over the popes when needed.29“Concordats in History,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th Ed. (1929), Vol. 6, p. 206. The right of the king not to be betrayed to agents of Rome was guarded very carefully against.30See A.D. 1267 below. Poor policy decisions that occurred in this time therefore, were attributable to the judgments of the sovereign monarchy.

Finally, the primary Investiture dispute was settled at the Concordat of Worms in 1122. Unlike that of London, this agreement became a destabilizing compromise and changed the political balance. The emperor kept his rights in his personal sub-kingdom of Germany, but he lost them in both kingdoms of Italy and Burgundy, where he remained emperor, but would no longer be allowed to select his own archbishops. Predictably his son Henry V reignited the controversy for his ancestral rights, and political fighting lasted until the end of Frederick II, the last Hohenstaufen. After Frederick’s death in 1250, the emperor’s authorities were degraded so far that no holder of that office would ever obtain absolute sovereignty over the lands that his family had.31“Germany,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 10, p. 252. Independent states sprang up in Central Europe, giving marginal recognitions and privileges to the later Emperors. Stronger polities, such as Italian city-states, and the Confederation of the Swiss would force themselves free from this, maintaining their own armies. Due to this situation, minor disputes would arise among the ruins of this empire, and factions for and against Rome would take sides in all of them.32“Guelphs and Ghibellines,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th Ed. (1929), Vol. 10, p. 947. The result then became that the state church was less monolithic after 1122, having a shorter reach than the Ottonian dynasty that it replaced had once been, as it had no clear head for over a hundred years, til the death of Frederick II. One thing that did change is that the state of Rome became an electorate, rather than a vassal, as it had been. The obvious contradiction remained in that this elected ruler was actually a fief-lord over part of central Italy including Rome. Therefore, this was a continuation of the state-church, as the two offices of overlord and archbishop were now merged.

c. A.D. 1119: Petrobrusian and Henrician uprising

Starting in around 1119, a powerful resistance occurred in the south of France against state church appointments. At issue were the Roman state church doctrines of infant baptism, the rite of Communion, prayers for the dead and icon venerations, which were proclaimed as idolatry. Many Petrobrusians in the south and east of France, objected to these appointments and insisted that one must be baptised after a profession of faith. A contemporary writer, Peter the Venerable33Peter of Cluny, writing in A.D. 1146, gives an explanation of their doctrine:

“They say, Christ sending his disciples to preach, says in the gospel, ‘Go ye out into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature: He that believeth, and is baptized, shall be saved; but he that believeth not shall be damned.’ From these words of our Saviour it is plain that none can be saved, unless he believe, and be baptized; that is, have both christian faith and baptism; for not one of these, but both together, does save: so that infants, though they be by you baptized, yet since by reason of their age they cannot believe, are not saved. It is therefore an idle and vain thing, for you to wash persons with water, at such a time when you may indeed cleanse their skin from dirt in a human manner, but not purge their souls from sin: But we do stay till the proper time of faith; and when a person is capable to know his God, and believe in him, then we do, not as you charge us, re-baptize him, but baptize him; for he is so to be accounted, as not yet baptized, who is not washed with that baptism, by which sins are done away.”34“Epistola Sive Tractatus adversus Petrobrusianos Haereticos” in Patrologia Latina, Vol. 189, col. 728-729.

Leaders of this movement were Peter of Bruys, active throughout the south of France during the early stages, and Henry of Lausanne, who was sometimes called by his opponents Henry of Bruys,35“Henry of Lausanne,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th Ed. (1929), Vol. 11, p. 448.36The same was also called “Henry of Toulouse/of Toulouze” in many older documents. as he continued the controversy after Peter was killed in 1126 at Saint-Gilles. Henry was known to have traveled further north, into Le Mans and Poitiers before eventually being arrested in 1134. The uprising or controversy was still ongoing fully in areas such as Languedoc as of 1163,37“Anno 1163. He caused some Decrees likewise to be made against the Hereticks who had spread themselves over all the Province of Languedoc. There were especially of two sorts. The one Ignorant, and withall addicted to Lewdness and Villanies, their Errors gross and filthy, and these were a kind of Manicheans. The others more Learned, less irregular, and very far from such filthiness, held almost the same Doctrines as the Calvinists, and were properly Henricians and Vaudois. The People who could not distinguish them, gave them alike names, that is to say, called them Cathares, Patarins, Boulgres or Bulgares…” Mézeray, Abbregé chronologique, ou Extraict de l’histoire de France, Tome III, p. 89. and there is no record of any settlement ending this controversy which some people had with the Roman-appointed leaders and bishops.

The Papal faction was also dealing with populist uprisings against them around the same time in Italy, as so-called “Arnoldist” leaders and everyday civilians had taken control of the city of Rome, establishing the short-lived “Commune of Rome” by taking over the city during 1144-1188.38“Arnold of Brescia,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 2, p. 455. Each of these incidents, despite occurring at roughly the same time span for the same reason, are rather unusually treated in Roman state records as separate and unrelated outbreaks of heresy. Each instance of rejection of their policies at that time is typically labelled according to various leaders of the movements, and the doctrines of those that proceeded with them were impugned with various accusations of gnosticism.39Allix, Remarks upon the ancient Churches of the Albigenses, p. 138. Although there was indisputably a presence of gnosticism around this time, that is not the whole story- and there is good reason to believe that most of these accusations were false. At the same time, there is clearly a common thread between these contemporaneous groups by the objections that they are known to have raised regarding baptism (and particularly, the rejection of infant baptism) as well as other doctrinal matters of significance.40In Allix’s remarks, we find that Alanus of Lille ‘confounded’ the doctrines of the Arnoldistæ together with the Cathari, and in both cases charged, “that they believed that Baptism is of no use to infants,” see Allix, Remarks upon the Ecclesiastical History of the Ancient Churches of Piedmont, p. 170. Each of the uprisings mentioned so far also rejected new Roman appointments of leaders to govern them, as well as their churches- something that had not been done in the former era when the state of Rome had held a vassal status, being entirely subject to the Emperors. So, this change from the emperor to the pope would serve a common motivation behind the political reactions in different regions about this time. The state church from Rome, led by a new figurehead, was not willing to be so lenient as the German state church had been.41“Muratori confirms […] the principality was constantly passing under different sovereigns, and that the people took advantage of these changes to obtain grants favourable to their rights and privileges.” W. Gilly, Waldensian Researches during a Second Visit to the Vaudois of Piedmont, p. 74.

*As one example of popular mislabelling in official documents, consider that the Arnoldists in Rome were also being labelled Poplecans, as reference to the Paulician uprisings which had occurred in Armenia, centuries earlier; this was charged as if what was happening in Rome were a continuation of a much more obscure group- a group which had likewise already been charged with gnosticism.

†A historical pattern is established, where serious opposition to the state church of Rome is labelled according to a contemporaneous leader, and when necessary, derided either as a rival state church to itself, or else charged with gnosticism. These labels serve a propagandist purpose, and are known to be not accurate, as may easily be shown by fuller examination of the evidence. The reality behind the situation is that there have, simply, always been conscientious Christian objectors to the state church from fourth century until now, who also oppose its policy of baptising infants, as well as its various alterations to scripture. It must be through these Christians that the uncorrupted Scriptures were preserved and kept available until now – which provides an answer to the question of where the “received text” of Scripture comes from.

Division along these lines, indeed, predates Peter of Bruys in these “Italian” and “Occitanian” regions, as evidence for the dispute reaches back to the year 1025 by an older group42Allix, Some Remarks upon the Ecclesiastical History of the Ancient Churches of Piedmont, pp. 102,110. (also holding the baptist distinctives43Synod of Arras: “But if any shall say, that some sacrament lies hid in Baptism, the force of that is taken off by these three causes: […] The third, because a strange will, a strange faith, and a strange confession do not seem to belong to, or be of any advantage to a little child [parvulum], who neither wills nor runs, who knows nothing of faith, and is altogether ignorant of his own salvation, in whom there can be no desire of regeneration, and from whom no confession of faith can be expected.” in ibid., p. 104.) which are part of a larger group of Christians which was later labeled as Paterines.44ibid., p. 122.45General History of the Christian Religion and Church: From the German of Dr. Augustus Neander, Vol. 4, p. 592. Although false doctrines were also attributed to this group. See appendix D for further information. The signal dispute against the metropolitan clergy in the region appears to pre-exist this further still, to an obscure group known simply as “Prophets,” which was in A.D. 945 denounced by Atto of Vercelli, for “by the words of simple brutes [having] left the holy mother Church, that is, the priests,”46Spicilegium of Dacherius (Ed. 1723), Vol. 1, p. 434.. Information as to what these “Prophets” did except for leaving the state church priests is not given there.

Turning to the records of state churches of these times, there is more evidence suggesting that the practice of paedobaptism (that is, infant baptism) had not yet firmly spread or established itself through all state churches before the ninth century. From Joseph de Vicecomes, a paedobaptist writing in 1620, we gather the following:

“Alcuin, in the chapter on baptism, writes: ‘For the purpose of the baptism of the elect, who are examined, according to the rule of the apostles, consecrated by fasting, and instructed by diligent preaching, two seasons are set apart, [namely] Easter and Whitsuntide.’ If these examinations were held according to the rules of the apostles, they must needs have been observed; but subsequently, when infant baptism came into vogue, this necessary practice was abolished by the church. A. D. 860, in the reign of the Emperors Lothaire and Louis; of which abundant proof exists.”47J. Vicecomes, Observationes Ecclesiasticae de Baptismo, Confirmatione, & de Missa, Vol. 1, l. 3, p. 262.

So by this account, state church policy regarding baptism, whether it was to be an infant or a believer, it was still in an undecided state within the Carolingian state church – in Germany and Burgundy. This accords with our earlier understanding that the Roman law of Justinian had not had any time to establish in these “barbarian” areas. This also accords with other accounts of officials of the time, who protested often and severely against some of the Frankish-installed popes.48“Recorded in the year 858. Guntherus, Bishop of Cologne, writes to the Pope Nicolas, ‘he plays the tyrant, under the habit of a Shepherd, but we know that he is a wolf: his Title is called Father, but to you he shows himself as a Jupiter,’ &c.”

from: Samuel Veltius, Gheslacht-Register, Van der Roomscher Pausen Successie, p. 127.49“Recorded in the year 900. Tergandus, Bishop of Trier: calls the Pope of Rome, the Antichrist, a Wolf, and [calls] Rome Babylon, a usurper of the ruler, a deceiver of Christians.”

from: Samuel Veltius, Gheslacht-Register, Van der Roomscher Pausen Successie, p. 128.50Two synods held by Lothair II in 862 (Aachen) and 863 (Metz) were annulled by the pope in 867. The sharply fallen state of affairs of this time, with the Frankish Empire then divided into three equitable parts, made room for the Roman bishop to intervene— king Charles the Bald, in the west, took sides with the pope, while the king to the east, Louis the German, sided with Lothair II in the dispute. However, both parties in the dispute were dead by 869 and the short-lived “central” kingdom was divided between its two neighbors. If the Roman mode of infant baptism had not fully extended beyond the borders of the Ravenna exarchate, it would explain why it wasn’t established even in the state churches of Francia, lands to the north and west of Italy, until around 860. It comes as little surprise that we find followers of “the Italian, Gundulf” (see the above appendix) free to send evangelists to Arras, nor, afterward, some Petrobrusians or Henricians defending themselves against the recent, strange impositions by the decrees of an overlord, which had until recent times been a vassal of the emperor. Peter of Cluny explained according to his account in A.D. 1146, they were also “anabaptists.”51“Epistola Sive Tractatus adversus Petrobrusianos Haereticos” in: Patrologia Latina, Vol. 189, col. 728-729. See translation given above.

These sentiments are comprehensible as reactions against the new forms of governmental interference that came in the aftermath of the Concordat of Worms in 1122, not among the least of which is forced infant baptism. Likewise, image worship had also likewise long been denounced in the provinces.52“Year 792, Charles king of France sent to Britain the book of the synod directly from Constantinople. In the book, alas, unfortunately! Many things inconvenient and contrary to the findings of the true faith, most of all that nearly all oriental scholars, no fewer than three hundred bishops, have mandated episcopal commissions requiring the worship of images, which is excerable to the church of God. Contrary to what they wrote, Alcuin has confirmed wonderfully from the authority of the Divine scriptures, against the same book which the king of France has brought to our princes and bishops.”

in: Symeonis Dunelmensis Opera et Collectanea, Vol. 1, p. 30.53Agobard, Liber Contra Eorem Superstitionem qui picturis et imaginibus sanctorum adorationis obsequium deferendum putant, in: Patrologia Latina, Vol. 104, col. 199-228.54Florus of Lyons, Opuscula Adversus Amalarium, in: Patrologia Latina, Vol. 119, col. 71-96. Therefore Peter of Bruys was not teaching anything new- the new thing in those years is the appointment of officials from Rome to impose new ideas such as infant baptism and images to the region by force. And it is simply a fact that not every person was going along with this.

A.D. 1209: First Albigensian Crusade

At the start of the 13th century, the Roman Catholic state launched an invasion into southern France, in the domain of the Count of Toulouse— not yet incorporated at that time into the domain of the crown of the kings of France.

This is none other than the very same region where the Henrician uprising had been ongoing (as we read before) as late as the year A.D. 1163, with no signs of stopping.

At some point in the 12th century, various gnostic ideas had spread through the towns of the area, due to the religious liberty allowed under Count Raymond VI of Toulouse. This would later become the pretext for an invasion and papal crusade against the rebaptizandi which had evaded Justinian’s grasp — as the historian Mézeray notes, that the gnostics were regularly confused and confounded with the baptists.55“Anno 1163. He caused some Decrees likewise to be made against the Hereticks who had spread themselves over all the Province of Languedoc. There were especially of two sorts. The one Ignorant, and withall addicted to Lewdness and Villanies, their Errors gross and filthy, and these were a kind of Manicheans. The others more Learned, less irregular, and very far from such filthiness, held almost the same Doctrines as the Calvinists, and were properly Henricians and Vaudois. The People who could not distinguish them, gave them alike names, that is to say, called them Cathares, Patarins, Boulgres or Bulgares…” Mézeray, Abbregé chronologique, ou Extraict de l’histoire de France, Tome III, p. 89. With the exception of Peter of Cluny’s description of their practice in 1146, we see similar mistakes, mistakes just as Mézeray describes, in state church literature of the time.56In A.D. 1179, an edict says “those whom some call the Cathars, others the Patarenes, … [have] grown so strong in Gascony and the regions of Albi and Toulouse…” See: Third Lateran Council (1179), article 27.57In A.D. 1184, an edict says: “Cathari and Patarines and those Humiliati or the Poor of Lyons, with the false name of Passagines, Josephines, Arnoldists, lie under a perpetual anathema.” See: Ad Abolendam (1184).58An encyclopedia states: “All who differed from the church of Rome, however much they might differ from each other, were comprehended under this denomination. This may also account for the great variety of appellations by which the Albigenses were known; for they were called by different authors, Henricians, Abelardists, Catharests, Publicans, and Bulgarians; […] They are also frequently confounded with the Waldenses.”

In: “Albigenses,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 1, p. 368. Yet we also know that the Patarines had allegedly appeared as early as the year 1025, when two of their evangelists (sent, as they confessed, by the Italian ‘Gundulf’) were interrogated at the Synod of Arras59Allix, Some Remarks upon the Ecclesiastical History of the Ancient Churches of Piedmont, pp. 102, 110., also that these were of the same belief and heritage as were later called the Vaudois or Waldenses.60ibid. p. 122. This second fact is confirmed by the inclusion of those two both as the same church, comprehended under different names in Ad Abolendam (1184), in our previous footnote (note: the “Poor of Lyons” was another derogatory name for the Vaudois61i.e. as having all of their property taken away was one of the punishments, they were subsequently derided for having little property).

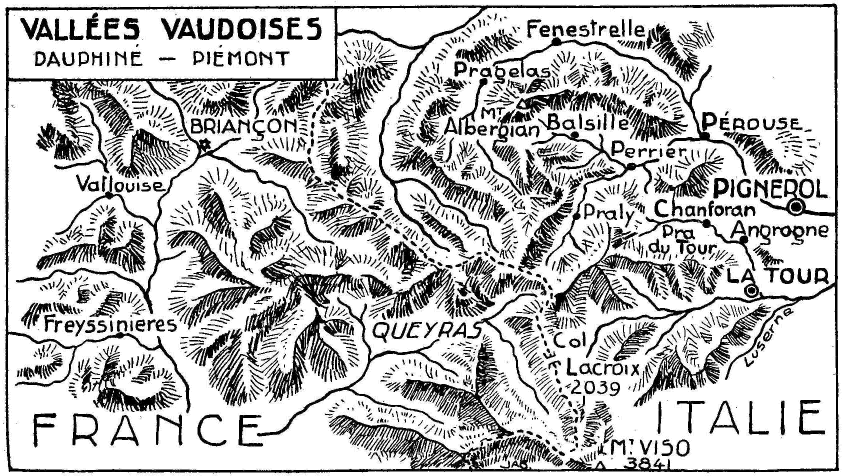

We have then three prominent groups living in the domain of Toulouse on the eve of this first crusade in 1209: First, catholics of the various state churches; second, the gnostic Cathars; Third: Petrobrusians or Henricians (formerly known as Paterines, and ‘rebaptizandi’, which is another word for anabaptists, anciently). The heritage of this third group would later outlive the Crusade, by turning to the Valleys of Piedmont within Savoy, bordering to the east of this region; In later times, the surviving remnant of these churches were known as Vaudois, meaning, “those dwelling in the valleys.”62For unequivocal proof of this etymology, see: Monastier, A history of the Vaudois Church, translated from the French (1848 ed.), pp. 53-62.

A peculiar event of the initial invasion of 1209, involves the battle or massacre of Béziers. On the first day of the army’s arrival, this first city fell into the hands of the crusaders. Caesarius of Heisterbach, writing from Westphalia about thirteen years after these events, relates the following account:

“When they discovered, from the admissions of some of them, that there were Catholics mingled with the heretics they said to the abbot ‘Sir, what shall we do, for we cannot distinguish between the faithful and the heretics.’ The abbot, like the others, was afraid that many, in fear of death, would pretend to be catholics, and after their departure, would return to their heresy, and is said to have replied ‘Kill them all, for the Lord knoweth them that are his (2 Tim. ii. 19)’ so countless number in that town were slain.”63Strange, J., Dialogus miraculorum V, ch. XXI, Vol. 1, p. 302.

The crusade saw prolonged warfare, as Count Raymond VI later regained control over the capital. Raymond VI had lost it for some time to Simon V de Montfort, who was a Roman-backed candidate intended to replace him. Simon V died while besieging Toulouse in 1218, a man perhaps accursed by the atrocities he committed.

A.D. 1229: Inquisition established

Even before the first phase of the Albigensian Crusade was over, the Pope brought fresh requests for a renewed crusade. This time, the plan was to annex the region to France. This brought a renewed assault from the French in 1225.

The count Raymond VII did not resist the onslaught for long, and in 1229, he decided to sue for peace, where he ceded the greater part of his lands to France. The rest was to be inherited from him on his death, if he were obedient to France and acted to assassinate nonconforming Christians. At this point, the Inquisition was set up to seek out all non-Catholic Christians in as many lands as possible, especially in southern France. The “inquisitors” were commissioned, a sort of prosecutor with unlimited immunities, and the state64typically the local Catholic bishop participated by carrying out the executions. This was started at the Council of Toulouse, 1229. Banned from possession were all Bibles.65“We prohibit also that the laity should be permitted to have the books of the Old and the New Testament…” Council of Toulouse, 1229, Canon 14. This was its response to the translation of the whole Bible that had been paid for by Peter Valdo in the previous century. Information on how widely Valdo’s translation had been spread is now difficult to determine. Another legal article of interest is the following:

“It is prohibited by a perpetual edict: Not by the laity, but rather by the canons of the Pontiff shall elections66for church office be decided.

If an election should, perhaps, be undertaken, it shall have no force: notwithstanding the fact this may be contrary to the custom, it ought rather be called the corruption of things.”67From: Decretals of Gregory IX. 1. c.c. 56.

By this decree, it was imposed upon the churches that all offices of the growing state church were to be appointed by the pope himself. Furthermore, votes by the local church to elect their pastors were now being called a corruption. Not long after this, the supposed right of the popes to replace even the leader or king of a nation and for the pope to dissolve all loyalties to that leader or king was retroactively reasoned by Thomas Aquinas, as can be found in one isolated entry in his book, Summa Theologica – Under the section on “oaths”:

“Sometimes what is promised under an oath is such, that there is doubt about whether it is right or wrong, advantageous or harmful, either in itself or under a particular circumstance; In a case like this, any bishop can grant a dispensation [of the oath]. Sometimes, however, what is promised under an oath is something that is clearly lawful and useful; And in a case of this sort there seems to be no room for a dispensation or commutation [of the oath], unless something better to do for the common good comes up, which would seem to pertain especially to the power of the Pope, who has the charge of the universal Church; even an absolute relaxation [of the oath], for this too belongs to the Pope in all matters of ecclesiastical administration, over which he has the fullness of power. In fact, any man may cancel an oath made by one of his subjects in matters that come under his jurisdiction; for instance a father may annul his daughter’s oath (Numbers 30:6), and a husband his wife’s, as stated above with regard to vows.”68Summa Theologica, Secunda Secundae, question 89, answer 9.

Now it happened in A.D. 1252, that additional grants were given to the inquisitors in which they were permitted to torture their captives in order to acquire information from them. This was followed soon by an inquisitor’s manual or handbook, of which copies still survive today. The author of this is attributed the name Pseudo-Reinerius, and it was probably written sometime around 1254-1259 in Passau. In it, a straightforward account is given about the doctrine of the Waldenses from this time period.

“Reineri, Ordinis Praedicatorum Liber Contra Waldenses Haereticos, Ch. IV.

“-The sects of the ancient heretics.

“Among the sects of ancient heretics, there have been more than seventy: all of which, thanks to God, have been destroyed, except the sects of the Manicheans, the Arians, the Runcarians and the Leonists, which have infected Germany. Among all the sects, which are, or which have been, there is none more pernicious to the Church, than that of the Leonists. This is for three reasons. The first reason is; because it is the more ancient69diuturnior among them: for some say, that it has lasted from the time of Sylvester; others, from the time of the Apostles.

“The second reason is; because it is more general: for there is hardly any land, in which this sect is not. The third reason is; because, While all other sects, through the enormity of their blasphemies against God, strike horror into their audience, this the way of the Leonists, has a great appearance of piety; the fact that they live justly before men, and they believe all good things about God, as are contained in the articles of the Creed; only they blaspheme the Roman Church, and Clergy, which the multitude of the Laity are ready enough to believe. And as we read in the book of Judges; Samson caught many different foxes, but tied their tails together: so the heretics, by sects, are divided among themselves, but in impugning the Church, are united. If heretics should be in one house, each of the sects condemns the other, at the same time the Roman Church attacks: And so it subdues the little foxes, and the vineyard of the Lord, that is, the Church, is purged of error.”70Jacobi Gretseri, Opera Omnia (1738 ed.), Tome XII, Pars Posterior (book 2), Index 1, pp. 27-28.

The authenticity of this book is not all that surprising. Since this was an inquisitor’s manual, it was written for professional use, not for propaganda. This is clear from the lack of any attempts by Pseudo-Reineri to cloud the pure reputation of these Leonists;71before they were called Vaudois, or Waldenses he is not spreading propaganda here, but wished to clear away any wrong expectations about these people, Christians, in advance for a new inquisitor reading this manual. We gain a better than normal insight from this document. All too often, in other publications there was an attempt to muddle these same Leonists in various official proclamations, and make them one party along with the Manichaeans or gnostics, so as to bring all into ill-repute— so to harm the reputation of the “Leonists” thereby, who were separate from the catholics. However as can be seen in this authentic mid-13th century document, they are treated differently when speaking candidly. They are treated as they are, simply as very pious Christian churches.

Picking up on the subject of the different names which the Vaudois – this same group – were originally called: to attempt to cast some light upon this hard subject we examine the Histoire des Vaudois, written by Jean-Paul Perrin in 1618. There, he relates the following:

“-The names that the Vaudois have been assigned by their adversaries, and what blasphemies they have charged them with.

“THE inquisitor monks, mortal enemies of the Vaudois, not being content to bind them every day with the secular arm, have also charged them with reproaches, respecting the heresies that are in the world, which they repudiate; and often [they] impute that such monsters were forged only from the Vaudois: as if only they72the Vaudois had been the vessels of all errors.

“They therefore first called them, from Valdo a citizen of Lyons, Vaudois: and from the country of Albi, Albigeois.73Albigensians

“In Dauphine they were called Chaignards by mockery.

“Also because a part of them crossed the Alps, they were called Tramontains.

“And for one of the disciples of Valdo named Joseph, who pressed in Dauphine to the bishopric of Dye, they were called Josephites.

“In England Lollards, named after Lollard who taught there.

“Of two pastors who taught the doctrine of Valdo in Languedoc named Henry and Esperon, they were called Henricians and Esperonnistes.

“From one of the Barbes who preached in Albigeois named Arnaud Hot, they were called Arnoldists.74Here is a marginal note by Mellinus (1619), marked ‘Arnoldus de Brixia’: “He also taught completely differently concerning the sacraments of the altar and of biblical infant baptism compared to past church teaching: no doubt in this respect he did the same service as Peter of Bruys, and Henry of Toulouse— denying transubstantiation, and denying that the mass is a sacrifice for the living and the dead: and that neither baptism nor the faith of others saves infants [jonge kinderen], just as we have read of Peter of Bruys.” Mellinus, A., Eerste deel van het Groot recht-ghevoelende Christen Martelaers-Boeck (Amsterdam, 1619), p. 425r, col. 3.

“In Provence they were called Siccars, from an unknown tongue that means purse-snatchers.

“In Italy they were called Fraticelli,75More of this group in A.D. 1262 below. It is possible this is an accurate reference to some Vaudois who were confused with this group. that is, little brothers, because they lived as brothers in true unity.

“Also, as they observed no other day of rest than Sunday, they were called Insabathas, because they did not observe the Sabbaths.76Another possible reason for this name, see Blair, in History of the Waldenses: “They wore a habit of white or grey, with shoes open at the top, and were by a mark distinguished from the poor men of Lyons or Waldenses, who, from this part of their dress, were sometimes called ‘insabatati’. Gretzer considers the Spanish name for the Albigenses, to wit, Xabatati, Xabatenses and Chabatati, as from Xabata, Chabata, or Chapata, shoes, which Ebrard and others call sotulares […] May not Insabatati just mean those people who have sandals on, or a peculiar shoe?” op. cit. pp. 384-385. The wooden shoes of the working and lower classes in the Netherlands were also called sabot.

“And because they were exposed to continuous suffering, they were called Patarenians or Sufferers, from the Latin word Pati, which means to suffer.

“And since, as momentary passengers, they fled from one place to another, they were called Passagenes.

“In Germany, they are called Gazares, a word which means excerable and insignificant.

“In Flanders, they are called Turlupins, inhabitants with wolves, because on account of persecution, they were often forced to live in woods and deserts.

“Sometimes they were named from the countries and regions they inhabit, such as: from Albi, Albigeois; from Toulouse, Toulousains; from Lombardy, Lombards; from Picardy, Picards; from Lyons, Leonists; from Bohemia, Bohemians.

“Sometimes to make them more execrable, they make them accomplices of the ancient heretics, but nevertheless under ridiculous pretexts. For as much as they make profession of purity in their life and belief, they call them Cathars. And because they deny that the host of the monstrous Priest at the Mass is God, they have called them Arians, with respect to the Divinity of the eternal Son of God; And when they rejoined that the authority of the Emperors and Kings of the earth does not depend on the authority of the Popes, they called them Manichaeans, as constituting two principles. And for other such imaginary causes they have likewise called them Gnostics, Cataphrygians, Adamites, and Apostolics.”77Perrin, Jean-Paul, Histoire des Vaudois (1618), pt. 1, chapter III, pp. 7-10. [on ‘insabatati’: please read appendix E.]

As we previously mentioned, it was after the times of inquisition that the people came to be called Vaudois. The surname, from thereafter crystallized into its current meaning, signified those remnants that outlasted the Inquisition, in an area, from where once, there had been many and widespread. As we read, the remote Valleys where they lived on the Alpine slopes, were both remote and difficult to access for large bodies of armed forces. In this region, through some succeeding centuries, a lineage of Biblical scholarship passed, from man to man, eventually into the halls of the academy in Geneva, a location bordering on the north of these Valleys, in the time of Calvin and Beza. This is of some interest to us because we can trace from here the Geneva Bible translated to English in 1557, which became an influence on the Authorized King James Bible.78For many years in Scotland, it was required by law for every household with sufficient means, to possess one of this translation of the Bible

Very revealing with respect to the position of these “anabaptists” on baptism, and other doctrines, are the corresponding records found in many neighboring countries at this time: See the letter of Everwin of Steinfeld, dated A.D. 1143, written in appendix F; and the Council of Oxford, dated A.D. 1160, which we have here written in appendix G.

Carrying on from the Council of Oxford decision in 1160, where the chroniclist William of Newburgh writes, “And this rigorous severity cleansed the kingdom of England from the creeping pest, but also prevented its future intrusion,” we see that this was very evidently not the case. From Roger of Howden, another chronicler, is recorded:

“[A.D. 1182] About the time at which this vision took place many of the ‘Publicani’ heretics were burned in many places throughout the kingdom of France, a thing that the king would in nowise allow in his territories, although there were great numbers of them.”79Riley, Henry T, The Annals of Roger de Hoveden, Translated from the Latin, Vol. 2, p. 20.

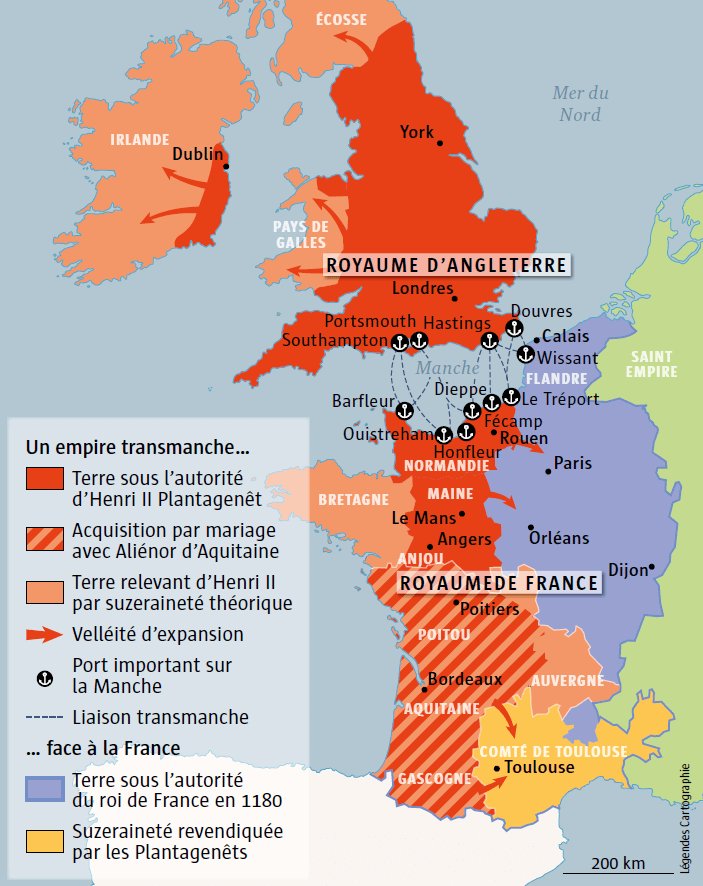

Whether the people in this account were located on the isle of Britain, over which Henry II was king, or in his French domains (which took up about the western half of that country) is unclear. But it was possible for population to transfer to and from England through this connection. This was then called the Angevin Empire. Part of these domains, especially in Gascony in the south-west, were connected to England until 1453, when France annexed the rest. This provided a means of escape from southern France through Gascony to England.

However, it is certain that this act did not manage to remove them all from the kingdom, nor did it prevent them from continuing to be present; because, in another place, Henry Knighton, another chronicler, gives this short entry:80Henry Knighton, Chronicon de Eventibus Angliæ (c. 1396), edited by Lumby, J.R., printed in London (ed. 1889), vol. 1, p. 185.

“(Year 1208.) Certain Albigensian heretics came to England, of whom some were burnt alive.”

This atrocity was in the year 1208, just one year prior to the Crusade, suggesting that some may have escaped from the impending Crusade out of southern France, in this direction, where some of the refugees were burnt alive presumably by order of the king or his delegates. The chronicle entry here specifically says they were Albigensians and that they came to England. However this cannot have removed them, as the London Chronicle, another chronicle by another author, tells us this:81John Bale, Scriptorum illustrium maioris Brytanniae, Vol. 3, p. 258. Contains quote of London Chronicle.

“Albigensians, which infected England, have reviled the clergy, on account of which one man was burnt alive at London in the year of our Lord 1210.”

We see from these accounts that these people were not absent in Britain, but they were found within England itself, so that one of them was burnt alive in London. The account says there were multiple of them. Now, we might give one last example which appears to us with special significance for this period, which is the following account. Of events in Strasbourg at around this same time, the following record was found:82Hugwald, Ulrich, De Germanorum prima origine. moribus, institutis, legibus, (1539), lib. 19, p. 196.

“In the year of our Lord 1212, there was a heresy in Alsace by which both the nobles and the common were led astray. They affirmed that it is lawful to eat flesh every day of the year, and that there is as much excess in the immoderate consumption of fish, as of meat in general; also, that it is an evil thing to prohibit marriage, since God has created all things, and all holy things may be received with thanksgiving by them which believe. They tenaciously defended this opinion, and a multitude believed them; and doubtless they blasphemed the holy lord the Pope because he forbade ecclesiastical persons from marrying and commanded them to abstain from certain kinds of food on certain days. Thus the Pope of Rome commanded that these men should be taken away. On a certain day, about one hundred men were burnt together by the bishop of Strasbourg.”

Though the above Chronicle mentions nothing of it, we must make notice the similarity of a Biblical passage, with this event, especially the underlined section.

1 Timothy 4:1-5

1 Now the Spirit speaketh expressly, that in the latter times some shall depart from the faith, giving heed to seducing spirits, and doctrines of devils;

Speaking lies in hypocrisy; having their conscience seared with a hot iron;

Forbidding to marry, and commanding to abstain from meats, which God hath created to be received with thanksgiving of them which believe and know the truth.

For every creature of God is good, and nothing to be refused, if it be received with thanksgiving:

For it is sanctified by the word of God and prayer.

The pinnacle of the Inquisition lasted until the Great Famines of 1315/1317. About that time, the Germans elected Louis IV who was solidified in his claim after the Battle of Mühldorf. Louis IV then created a rival pope in 1328, contributing in this way to the whole downfall in disgrace of that false religion.

To close this entry, soon after the original Council of Toulouse in 1229, indulgences also became widespread, as local peddlers would make contracts with the officials in each area for the business of selling indulgences, which were sold reportedly for a single mite. This deterioration to this situation was denounced by the last generations of troubadours which still spoke the local Provençal language in Toulouse, southern France and its surrounding towns:

“The clergy call themselves pastors and are butchers. Kings and Emperors once used to rule the world: now priests exercise lordship with theft and treason — with hypocrisy, force and threats. They are not satisfied unless every thing is surrendered to their hands, and, though there be delay, in the end it is brought about. The higher their rank, so much the less virtue they possess and the more folly, the less truthfulness and the more falsehood, the less learning and the more faults, and withal so much the less courtesy. —The priests are so full of ambition, that they can not bear to see any one in the whole world hold sway except themselves. They work with all their might to draw over the whole world to themselves, whoever may be the sufferer; they win such persons with obsequiousness and gifts — with pardons and hypocrisy — with indulgences — with eating and drinking — with preaching and cursing — with God and the devil. Vultures and birds of prey scent not the mouldering carrion so swiftly as they scent a rich man. Immediately he is their friend; sickness lays him low, he must heap gifts on them to the prejudice of his relations. Frenchmen and priests gain the praise of superior wickedness.”83F. Diez, Leben und Werke der Troubadours, p. 446. — Peire Cardenal, troubadour (fl. 1220)

“Rome, you make it a game to send Christians to martyrdom. But in which book have you read, that you must exterminate the Christians?

Rome, you are practicing nefarious sermons against Toulouse; ugly, like an angry snake, you wound the hands of the small and the great. Let the excellent count live for another two years, he shall make France repent for having submitted to your impostures.

Rome, it is my consolation that you will soon fall into ruin, when the Righteous Emperor shines forth and does as he should; truly, Rome, you will see your power crumble! God, save the world let me experience that soon!”84ibid., pp. 565-566. — Guillem Figueira, troubadour (fl. 1244)

“Ha, ye false priests, liars, traitors, perjurers, whoremongers, infidels, so much open wickedness ye work day by day, that ye have thrown the whole world into consternation. St. Peter never drew revenues from France, nor extorted usury — no, he held upright the balance of justice. Ye do naught of the kind. For money ye unjustly pronounce and recall sentence of excommunication; without money there is no redemption for us.”85ibid., p. 587.

— Bertran Carbonel, troubadour (fl. 1255)

c. A.D. 1262: Antinomianism

Around this time, several shadowy groups of antinomianists first appear in the records. These were on matters of substance no different than the Manichaeans, who had previously been defeated militarily at Montségur,86the last of these gnostics perished in a siege at Montségur in the year 1244. yet they differed from these in various externalities. Many now openly affirmed the position of antinomianism (which can be summarized as, “the only sin is that which offends the conscience”) leading to the most horrendous of degenerate behavior. This is similar to what had resulted with the former Manichaeans87“Anno 1163. He caused some Decrees likewise to be made against the Hereticks who had spread themselves over all the Province of Languedoc. There were especially of two sorts. The one Ignorant, and withall addicted to Lewdness and Villanies, their Errors gross and filthy, and these were a kind of Manicheans. The others more Learned, less irregular, and very far from such filthiness, held almost the same Doctrines as the Calvinists, and were properly Henricians and Vaudois. The People who could not distinguish them, gave them alike names, that is to say, called them Cathares, Patarins, Boulgres or Bulgares…” Mézeray, Abbregé chronologique, ou Extraict de l’histoire de France, Tome III, p. 89. or Cathari and the ‘imperfecti.’88or “perfecti” as they would often call themselves Also like the medieval Cathari that came before them, the antinomians were murderous menaces, which provided a convenient casus belli (or cause of justification) to the inquisitors that also abounded in this era. We have little reason to doubt many of the horror stories regarding these groups. They were often conflated, whether intentional or mistakenly, with the regular, congregational and orderly Christian churches, which also were driven underground by the inquisitors. Sometimes the same slur was applied to both groups indiscriminately, just as “Albigensians” had originally been used, at the time, to portray both Vaudois and Manichaeans as though they were one group.89“Sometimes to make [the Vaudois] more execrable, they make them accomplices of the ancient heretics, but nevertheless under ridiculous pretexts. For as much as they make profession of purity in their life and belief, they call them Cathars. And because they deny that the host of the monstrous Priest at the Mass is God, they have called them Arians, with respect to the Divinity of the eternal Son of God; And when they rejoined that the authority of the Emperors and Kings of the earth does not depend on the authority of the Popes, they called them Manichaeans, as constituting two principles. And for other such imaginary causes they have likewise called them Gnostics…” in: Perrin, Jean-Paul, Histoire des Vaudois (1618), pt. 1, ch. III, pp. 9-10.

The primary group which emerged around this time were the Brethren of the Free Spirit. They appeared some time between 1262 and 1280. We have explained their belief: they taught that nothing is sin except what offends oneself. There is nothing else to say about that, nor a sharper possible condemnation, aside from what Scripture already tells.

Around 1263 another event related to this occurred, which we took a brief note of in the former entry: The appearance of another sect called Fraticelli.90“Fraticelli,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th ed. (1929), Vol. 9, p. 702. It is possible that at some point, some of the Vaudois were confused with this group which got its start in Italy. The story behind this is, a man named Gerard Segarelli was denied entry into the order of Franciscan friars, so around the year 1263 he gathered a large following of similar-minded spiritualists. Spiritualists are known by their claim to have personal revelations. So they reject the word of God in favor of their own ideas, even though these have nothing to do with scripture. Segarelli’s successor, Friar Dolcino, led the violent band into the Sesia valley, near Biella, Italy. When asked why he pillaged and butchered the people of this valley during his occupation, to this Dolcino replied: “To the pure all things are pure, but to the corrupt and unbelieving nothing is pure; their very minds and consciences are corrupted. – (Titus 1:5)”91See: 2 Pet. 3:16 “they that are unlearned and unstable wrest, as they do also the other scriptures, unto their own destruction.”

2 Sam. 1:16 “for thy mouth hath testified against thee,”

These groups of Friars called themselves Apostolics or Apostolical Brethren, because they insisted that their alleged voluntary poverty or other acts gave them freedom to violate every other commandment and law. Another early antinomian in this movement was named Angelo da Clareno, a man who got his start in Italy in 1278. From the records we can conclude that these were dissident monastics. These antinomians first appeared in Italy around 1263, and they mostly operated in the Mediterranean provinces. The antinomians are not to be confused with the Lollards of the Netherlands which we will discuss in the third article, although the latter may very well have been accused of being the same as them in some sources.

A.D. 1267: Statute of Marlborough

In 1267, the closing days of the Second Barons’ War, King Henry III restored peace to England by making a full commitment to the Magna Carta with this statute. The events that led up to this however, started in the year 1205.

Under King John (1199-1216), the archbishopric had been contested between two men who had both been elected by separate groups to fill the office. The pope chose this moment to strike and create a conflict between himself and the king, and he did this by nullifying both elections and having another chapter of Englishmen elect Stephen Langton to fill the office, and held him up as the true replacement. The king, weakened by his recent loss of Normandy to France, was opposed to this. He was obliged to oppose it, because this action challenged his right as king to make the selection. Soon many churchmen withdrew or were expelled from the domain of the English King, in response to the subsequent dispute that took place. However, King John lacked military support to a worse degree than he knew, so that his schemes were gradually outdone.

Through increasing pretensions, the pope eventually declared that the king of England was deposed from his rule of England. Then, in January of 1213 the pope gave the king of France the warrant and indulgences to invade the country, and to violently kill and destroy that land, just as he had done (or was going to do) to Toulouse in the south of France.

The king of France eagerly pursued this, gathering a navy of 1700 sails and summoning all the vassals of his kingdom in preparation for this invasion of England.92“England,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 8, pp. 613-614. Additionally, the English King John had just the prior year been forced to cancel his planned expedition into Wales by reports that many of his own barons were planning to take the other side against him. They were angry at his military losses and he stood accused of improprieties. Finally, giving in to fear, John came to Temple Ewell near Dover, England on May 15, 1213 to become a vassal and surrender his crown to the legate (representative) of the pope.

King John absolved on May 15, 1213

Immediately, the sides shifted. Now the nobles of the realm were opposed to not only France but also directly opposed to King John and the pope. The king meanwhile found himself with full and unrestrained papal support. In a turn that no one expected, Stephen Langton now took sides with the nobles, and met with them first at Westminster in August 25, 1213. They resolved themselves to uphold the privileges of the kingdom in opposition to any ruler who stood in their way.93“England,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 8, p. 614. Stephen then called to their attention the existence of a charter given by Henry I in 1100: the Charter of Liberties. It had guaranteed the rights of the subjects to retain the ancient laws of the land.94“England,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 8, pp. 602-603. This document had been written down from oral traditions by several individuals who had been in the kingdom before the invasion of 1066.

The events are described in this way:

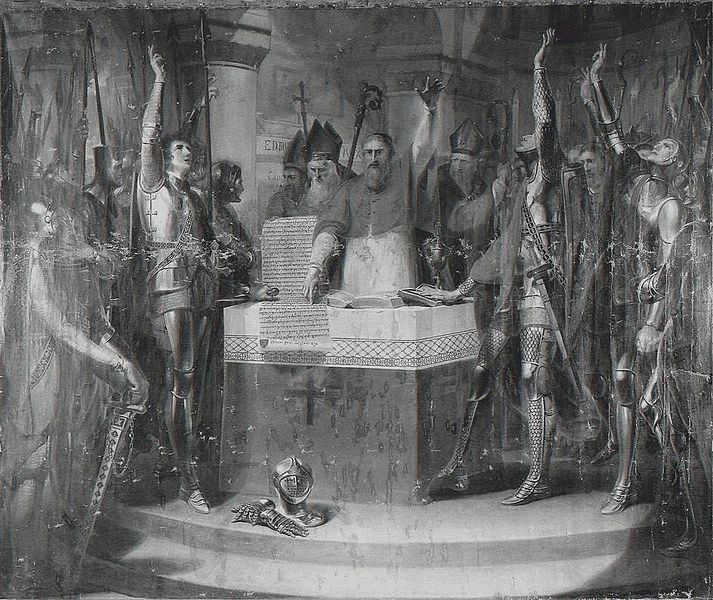

“The barons had entered into a confederacy for the restoration of their ancient privileges. They were encouraged and supported in their design by the archbishop of Canterbury, who, being of a generous and liberal spirit, was anxious to promote the real interests of the kingdom. At a numerous meeting of the barons summoned by him at St. Edmondsbury, under pretence of devotion, he produced an old charter of Henry I. of which he exorted them to demand the renewal and observance; and represented in such strong colours the arbitrary conduct of their sovereign, that they all swore before the high altar to support each other, and to make endless war upon the king, till he should grant their demands.”95“England,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 8, p. 614.

This second meeting took place on November 20, 1214 in Bury St. Edmunds, in Suffolk, England.96Flores historiarum (1570 ed.), pp. 95-96. A little known fact about this alliance of nobles is its name: ‘Army of God and Holy Church.’

The rebels had support from the population anywhere they went. John met with them in 1215, and after several revisions they agreed upon the first version of what would be called the Magna Carta and both parties signed it. However, John claimed it was signed under duress, and the pope upon hearing about it annulled his signature to the document. This led to the First Barons’ War, which didn’t end until John was dead, whereupon his young son quickly gained preference by the English populace over the French invader. This invading prince had landed in England and was still seeking to fight John and take the English throne for himself, ever since the pope had given him the original indulgences to invade.

As part of the path toward reconciliation with the rebels, the young Henry III proposed a new edition of the Magna Carta in 1216, which loosened some of the restrictions on the king, making it more a more realistic constitution. However, this proposal by the new king was not respected. However after peace had been achieved with France, as a final gesture of reconciliation, Henry issued the Magna Carta libertatum (along with the Charter of the Forest) in 1217. This 1217 version is often cited as the original Magna Carta.

However, at a later opportunity, Henry III claimed that he had signed the document under duress, since he had only been ten years old in 1217 and he threatened to act in disregard to the charter. Thus in 1225, he signed a new edition of the charter, which was updated with the line that he had signed it of his “spontaneous and free will.” This was in return for additional taxes.

However, in 1227 at the age of twenty, Henry had himself proclaimed “of age and able to rule independently.” He announced that all future charters had to be issued under his seal, therefore raising questions over his 1225 agreement. He continued to threaten to overturn the law whenever it was convenient until 1253, when he signed a new edition of the charter in exchange for taxation. However, during this time he generally stayed close to the bounds of this law, so that his threat would remain potent.

Nevertheless, in 1258 there was a coup d’état against the king, led by barons who wanted a more strictly enforced charter. Notwithstanding this however, these barons’ proposal, called the Provisions of Oxford did not have a necessary level of approval, and ultimately the country slipped into the Second Barons’ War. Finally in 1267, the sixty-year-old king signed the Statute of Marlborough as part of the peace deal, which came with a full commitment to uphold the terms of the charter. His son Edward I also reconfirmed it again in 1297.97“Confirmatio Cartarum”

It is a lesser known fact, that the circumstances that brought about the writing and commitment to the principles of the Magna Carta, a document which is so remembered today, was the need to impede papal influence, as formerly cited from the Edinburgh Encylopedia from its article on England: “to promote the real interests of the kingdom.” Thus, the exhalations of threats breathed out from Rome seemed to lose their weight, and became as air upon reaching the solid shores of this island.

But this was not the only law passed in England in order to prevent exposure to these interferences from the ruler of Rome. Among the early acts of Edward I during his reign was to codify the whole law of England, along with the Charter, into 51 chapters.98Statute of Westminster, 1275 Additionally, he passed laws further intending to restrict foreign church land holdings.99Statutes of Mortmain, 1279 & 1290, although this was not entirely effective due to use of cestui que use and cestui que trust distinction See appendix H for an overview which we have copied by the lawmaker Sir William Blackstone on this history. The so-called Peter’s pence, a tax to Rome, was also paid for a very long time, until the year 1327 when the King ended this practice as well.

c. A.D. 1271: Beginnings of Secular Humanism

From around A.D. 1271 the syncretist Rаmоn Llull, a scholar of Arabic and other languages, begins to write works which acquire a more recognizably humanist tone than before.100“Lull, Rаimоn (c. 1235-1315),” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th ed. (1929), Vol. 14, p. 478.101“Chemistry, Raymond Lully,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 6, p. 3. Having drawn from many aspects of Islam, as well as tаlmudіsm and neoplatonist gnosticism, many of these works were reference points in the future fields of secular humanism, Catholicism, and rаbbіnіcal scholarship. Also in a key point of development for tаlmudіsm, the kаbbаlаh was expanded, with the Zohar being written in Iberia, year 1291.102“Kаbbаlаh, Works,” Encyclopædia Britannica 14th ed. (1929), Vol. 13, p. 234. These works especially emphasized the Gnostic Manichaean principle of unifying the ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ planes.103As exemplified in the identity of the false deity ‘Shеkhinаh’ which was said to represent this unification104“Eclectics,” Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Vol. 7, pp. 326-327.105Modern times: ‘Multiculturalism’

This is not a philosophy built on anything other than finding common ground between majorities of people, and thus at least in theory, winning a majority; which, some seem to suppose, in the absence of any firm truth such as the truth of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, will bring about their cause. See A.D. 242: Manichæism and A.D. 245: Neo-platonism in part one for more. End of part two.

Link: Part three (final) of this Outline

Appendix D

The following is written in Sacrorum Conciliorum Nova Amplissima Collectio,

Vol. 19, col. 424-425:

SYNODUS ATTREBATENSIS [The Synod of Arras, 1025.]

A Gerardo Cameracensi & Attrebatensi Episcopo celebrara anno MXXV

[translated from the Latin]

“In the year of our Lord 1025. Eighth indiction. To Lord Gerard of Cambray and Arras. It came about that after Christmas and Epiphany had been observed with solemn ceremony within the see of Cambrai, in accordance with the custom annually followed the Prelate was to stay for several days in the see of Arras. There, while they were performing appropriate church functions, he was informed that certain men had come to that locality from Italy, which were introducing certain new heretical doctrines, attempting to overthrow the instruction of evangelical and apostolical sanctions; they established a certain justice, asserting that men were purified by it alone, and that no other Sacrament in the Church could save them.

“On hearing these things, the lord Bishop sought to inquire of these men, and gave orders for them to be found. Upon hearing of their search, they prepared to leave secretly, but they were prevented by the magisters and drawn before the Bishop. Being occupied with other matters, he exchanged only a few words with them on their belief; perceiving that they were fascinated by certain wicked dogmatical errors, he ordered them to be held in custody until the third day; and the next day he imposed a fast on all clerics and Monks, that the grace of God might cause the prisoners to recover their understanding of the catholic faith.

“On the third day, which was a Sunday, the Bishop returned, together with his Archdeacons carrying crosses and gospel texts, surrounded by a great throng of all the clergy and people, proceeding to the church of blessed Mary to hold a great synod; after the antiphon ‘O God arise,’ the whole Psalm was completed. Then the Bishop sat in his consistory, as did each Lord Abbot, with his monks, and the Archdeacons on either side, and the rest, according to the rank of their ordination, according to their degree, and then the men were brought in. At first, the bishop made some general remarks about them to the people. Then, he turned to them with these words: ‘What,’ he asked, ‘is your doctrine? what is your law and way of life, and who is the originator of your discipline?’ They replied, that they were followers of one Gundulf, from certain parts of Italy, and that he had instructed them in the commandments of the gospel and the apostles, that they accepted no other scripture than what they had received, but to this they held in word and deed. However, the Bishop had in fact received notice of them, that they utterly abhorred the holy mystery of Baptism, that they rejected the sacrament of the body and blood of the Lord, that they denied the work of penance to the lapsed, that they openly maintained the invalidity of the church, that they cursed lawful marriages, that they saw no special power in the gifts of the holy Confessors, and that they thought none but the Apostles and martyrs should be venerated.

“On these things the Bishop asked: ‘How has it come to pass,’ he asked, ‘that what the evangelical and apostolic institutions hold, is contrary to what you preach?’ He narrated, ‘in the text of the gospel, unto the prince and Ruler Nicodemus, who regarded those signs and wonders as signifying that Jesus was of God, the Lord continued to answer, “that no confession alone could merit a role in the kingdom of heaven, unless a man be born again of water and the spirit.” So either you are able to receive regeneration from this mystery, or else the gospel words must conflict with what Jesus said.’

“To these things they gave this answer as follows: ‘The law and discipline we have received from our Master will not appear contrary either to the Gospel decrees or apostolical sanctions, if we carefully examine these. This discipline consists in leaving the world, in bridling carnal concupiscence, in providing our own livelihood by the labor of our hands, in seeking the harm or hurt of no one, and in affording our charity to our fellowservants who are of the same purpose. Now if we have safeguarded this righteousness, then Baptism will add nothing further to this; and if we have transgressed against this truth, then Baptism will not profit to salvation. This is our greatest justification, to which baptism can accrue nothing, for this is the end of all the apostolical and evangelical institutions. But if any man among you shall say, that some hidden sacrament lies within baptism, that is thrown off by three causes. First, because the reprobate life of the minister itself is not able to provide life to the person to be baptized. Second, because whatsoever sins are renounced at the font, shall be repeated later in life. Third, because a strange will, a strange faith, and a strange confession do not seem to belong to, or be of any advantage to a little child,106parvulum who neither wills nor runs, who knows nothing of faith, and is altogether ignorant of his own good and salvation, in whom there can be no desire of regeneration, and from whom no confession of faith can be expected.’

“And the Bishop responds: . . .” End quotation. [Because of this one response, they are afterward charged of Manichaeism, of dissolving marriages, and more…]

Note: The rest of chapter I, and then chapters II – XVI, consist entirely of the Bishop’s prepared remarks.107Note: Based on this historical record alone, there seems to be no reason to think the “Manichaean” or “gnostic” charge brought against these men had any substance to it beyond an accusation prepared in advance, which ought not to be readily believed.

In chapter 1, it is implicated that they rejected water baptism, and instead practiced foot washing.

In chapter 2, it is implicated that they rejected the Eucharist.

In chapter 3, it is implicated that they denied that a church is the house of God.

In chapter 4, it is implicated that they objected to the altar and the use of incense.

In chapter 5, it is implicated that they objected to the use of bells in churches.

In chapter 6, it is implicated that they objected to ordination.

In chapter 7, it is implicated that they objected to the use of holy burial grounds because of simony.

In chapter 8, it is implicated that they denied the efficacy of penance.

In chapter 9, it is implicated that they objected to prayers for the dead.

In chapter 10, it is implicated that they objected to the institution of marriage.

In chapter 11, it is implicated that they objected to auricular confession.

In chapter 12, it is implicated that they objected to psalmody in church services.

In chapter 13, it is implicated that they objected to veneration of the Cross.

In chapter 14, it is implicated that they objected to images of Christ on the Cross or saints because they were the work of human hands.

In chapter 15, it is implicated that they opposed the hierarchy.

In chapter 16, it is implicated that they held a heretical doctrine of justification.

In the conclusion, it is stated that the men are released after being “stunned into silence” and agreeing with all of the Bishop’s rebuttals.

No further record of direct testimony of the accused men exists. It is often assumed that the men were gnostics as the Bishop of Arras mantained against them. However, the only direct record of testimony from the accused men is recorded from the initial part of Chapter I, as given by the above translation.

Appendix E

The following is written in Maxima Bibliotheca Veterum Patrum,

Tome 25, p. 190:

“Aldephonsus Dei gratia…

[translated from the Latin]

-A.D. 1194

“Aldephonsus, by the grace of God, King of Aragon, and Count of Barcelona, and Margrave of Provence, to all Archbishops, Bishops, and all the rest of the Prelates of the Church of this Kingdom, to all the Earls, Viscounts, soldiers, and to the entire people of the kingdom and our dominion, greeting, and good wishes for the integrity of the Christian religion. As it has pleased God to place us over his people, it is right that we should take great concern to, according to our ability, tend to the salvation and defense of our people. For this reason, in faithful continuity with our predecessors, and in rightful obedience to the canons that all heretics before God and Catholicism should be cast down, condemned and persecuted— the Waldenses or Insabbatatos, who are called the Poor of Lyons, and all other heretics who are so many they are beyond numbering, have been anathematized by the holy Church, from all of our kingdom and dominion, as enemies of the Cross of Christ, a dishonor to the Christian religion and our person, and public enemies of the kingdom itself, and are commanded to go out and flee into exile. And from this day on, if any one shall meet and receive these Waldenses and Insabbatatos, or other heretics of whatever profession, into their homes, or listen to their deadly preaching in any place, or give them food, or dare to show them any other favor, then he has incurred the wrath of God omnipotent, and of ourselves, and his goods shall be confiscated without appeal, for he has committed the crime of lese majesty.

“This is our edict and the continuing ordinance for every city, castle and village in our kingdom and dominion, and throughout all the land of our jurisdiction, which shall be recited by the Bishops each Sunday; Church leaders, as well as Governors, Bailiffs, Justiciaries, Merinis, and Zafalmerinis, and all the people, shall observe it, so that the aforementioned penalty shall be inflicted upon all offenders. Be it further known, that if any person, noble or ignoble, shall find any of these wicked spirits anywhere in our lands, after the three days’ proclamation, who, knowing our decree, do not speedily depart, but rather remain stubbornly, then there shall be no punishment for any evil, disgrace, or hurt, except death or maiming, inflicted upon them; and he shall rather merit my favor, and he shall know that this is acceptable to us. We shall give a respite from this (though beyond their deserts, and against reason) until tomorrow, which is All Saints Day, to leave our land; and if any are found remaining, we give full lenience to rob and dispossess them, to fashion clubs and to beat them, to shamefully abuse them.”

Appendix F