This article will provide a brief outline of the history behind the English translation of the scriptures that we have today. Included in the second half is a review of the major and minor editions of the authorized version.

For our purposes in this article we can begin our history at the time of the apostles, and I have divided the remaining “time of the end”1Daniel 12:4, Rev. 22:10. into three time periods. Our first part concerns the early A.D. period, the second part covers the early English translations, and the third part covers the Bible under modern English or “proper” English, which will be defined below. Part four also contains some added research material mainly to supplement the third.

Page Index

Part 1: Timeline of the Bible before modern English

As the book of Acts records in the New Testament, the word of God began taking root in many languages on the day of Pentecost.2Acts 2:4-11 It is further related that the word of God “grew, and multiplied” during this time.3Acts 6:7, Acts 12:24, Acts 19:20. However, it must be that only a small portion of all that was spoken was written down into physical copies. Nevertheless, the watchful eye of God ensured that nothing of his inspiration was lost,4Isaiah 55:11, Matthew 24:35. so that the New Testament of today contains every prophecy, by its incorruptible nature.51 Peter 1:23-25 The original word has been transmitted and written down, copied numerous times, and translated accurately into other languages, with the Holy Spirit teaching the truth of those things unto his believers in every time.6John 16:13-14, 1 Corinthians 2:9-13.

The fact that the New Testament is in Koine Greek first, appears to help for two reasons. The first reason is because it was the trade language in the eastern Mediterranean region. This causes the gospel to be given in a well-known and well-defined language with many copyists in place to transmit it. Secondly, the grammatical structure of this language also allowed the precise word tenses to be encoded into the text of the Scripture.

For many ancient Europeans, the language most closely corresponding to Koine Greek at the time would be Classical Latin. Over time this became the scholarly language of the continent. It would remain in use by scholarship for more than a millenium after its fall into disuse as a spoken language.

F.H.A. Scrivener in his book Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament7Vol. 2, p. 43. draws specific attention to the use of Latin translations in northern Italy. He cites the Prolegomena of John Mill,8Novum testamentum græcum (1707), section 377 where Mill has dated the original Latin translations of the ancient churches as no later than the year A.D. 157. Scrivener also mentions the fact that Augustine of Hippo (A.D. 354-430) singled out this translation, which “deserved praise for its clearness and fidelity.” This body of translations is referred to as Vetus Latina, or sometimes the Old Italic translation. It now represents a textual family in Latin which predates the translation of Jerome9which eventually became a central component of the Vulgate by hundreds of years.

It is further told to us in the work of Beza10Histoire ecclesiastique des Eglises reformes au Royaume de France, Vol. 1, p. 53. that a community who lived near this region, known to the French as Vaudois, must deserve credit for France today having the Bible in her own language.11ibid., p. 53. “since the year 1535 they have printed at their expense, at Neuchatel in Switzerland, the first printed French Bible of our time […] As for the translation of French Bibles printed during the darkness of ignorance, this was only falsehood and barbarism.” These are people that lived in mountainous valleys in the region known as Savoy (in the part of it that is now in northern Italy), which is a certain distance to the south of Switzerland.

There are a few interesting points of comparison we can make before moving past the Latin formats. By the time of Jerome, a great number of Vetus Latina copies had already been circulating in the Latin world, many having been faithfully translated from their Greek counterpart. Meanwhile, there is a great amount of variance in the precursors to what we know as the Vulgate, which are only partially taken from the work of Jerome. His decision12which was criticized by Augustine to use the Hebrew for his Old Testament and not an intermediate Greek version, did not prevent his other separate translation of the Hexaplar Septuagint version of the Psalms from entering into the Vulgate. Because of this, the Vulgate also includes the removal of the prophecy of the Son in Psalm 2:12 (see article) where it writes “Apprehendite disciplinam” or “Embrace discipline”, instead of “Kiss the Son” as the verse is given in the original language.13“Kiss the Son, lest he be angry, and ye perish from the way, when his wrath is kindled but a little. Blessed are all they that put their trust in him.” — Psalm 2:12 Until the counter-reformation, there were many copies circulating of both Vetus Latina, and of the prototypical versions of Latin which finally became the Sixtine Vulgate in 1590. Thus 1590 is the earliest possible date for the “standard version” of the Vulgate, despite it often being suggested that the text body is much older. Widely known changes in this version are the addition of the word “again” in John 3:5,14“Jesus answered, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God.” — John 3:5 (manifested as “renatus” instead of “natus”), and the alteration of Matthew 6:1115“Give us this day our daily bread.”

— Matthew 6:11 against the Greek text, where “daily bread” was replaced by “supersubstantial bread.” In A.D. 1592, the Sixtine Vulgate was superceded by the Clementine Vulgate which contained various changes, but did nothing to correct the above. A small number of the textual variations in the Alexandrian texts16e.g.– Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus which were discovered much later can also be observed in this version.

Following up after the Latin is the Anglo-Saxon part of our history. Our closest source for British history following the collapse of the Roman empire there is the ancient source Gildas. His work De Excidio Britanniae remarks on the causes for which Germanic Angles and Saxons came to Britain. Regarding events of approximately the year A.D. 411, he wrote:17Op. cit., paragraph 18.

“The Romans, therefore, left the country, giving notice that they could no longer be harassed by such laborious expeditions, nor suffer the Roman standards, with so large and brave an army, to be worn out by sea and land by fighting against these unwarlike, plundering vagabonds; but that the islanders, inuring themselves to warlike weapons, and bravely fighting, should valiantly protect their country, their property, wives and children, and, what is dearer than these, their liberty and lives; that they should not suffer their hands to be tied behind their backs by a nation which, unless they were enervated by idleness and sloth, was not more powerful than themselves, but that they should arm those hands with buckler, sword, and spear, ready for the field of battle;”

Seeming to corroborate this, a Greek Byzantine chronicler Zosimus also mentioned it in his Historia Nova:18Book 6, paragraph 10.

“When Valens, the master of the horse, was killed after falling under suspicion of treason, Alaric attacked all the cities of Aemilia that had refused to accept promptly Attalus’ rule. He brought over with no trouble at all every one of them except Bononia [Bologna], which he besieged for several days but could not capture as it held firm. He then proceeded to the Ligurians and compelled them to recognise Attalus as Emperor. Honorius, however, wrote letters to the cities in Britain urging them to be on their guard, and he distributed rewards to the soldiers from moneys supplied him by Heraclianus.”

From this situation, Gildas attributes the decision by the king of the Britons to enlist mercenaries from Saxony to defend against the northerners, which are now known as the Picts and Gaels. This would have occurred in the early 5th century, some years after the withdrawal of the legions. Yet before this series of events, there is cause to believe that centers of Christian learning had already flourished on the island.

According to the entry for “Landwit-Major” in A Topographical Dictionary of Wales19Lewis, op. cit. (1834 ed.), Vol. 2, p. 4. it is recorded that a college was founded: Cor Tewdws,20College of Theodosius dating to the reign of Emperor Theodosius (A.D. 392-395). The false teacher Pelagius is traditionally said to have received education here. The original college was ransacked by an unknown war party around the middle of the 5th century, and according to some, is also where Patrick himself had been abducted into Ireland from.21“This institution was afterwards destroyed by a band of Irish pirates, who, landing on this part of the coast, carried away by violence its principal, Maenwyn, better known as St. Patrick, the apostle and tutelar saint of Ireland. Soon after this event, St. Germanus, who was sent into Britain by the Gallican bishops, to suppress the Pelagian heresy, and is supposed to have been hospitably entertained at Boverton, where the native reguli continued to reside occasionally (till the overthrow of their power by Robert Fitz-Hamon), associating the old college of Theodosius with the name of Pelagius, selected the site of that institution at Lantwit, then called Caer Wrgorn, for the foundation of one of those seminaries for the education of the British clergy…”

in: ibid. It is held also to have been re-established on the same spot by Illtud22or Iltutus around the year A.D. 508, and from then on became the center of learning for Britons (who later came to be called the Welsh) and where the aforementioned Gildas may have learned from. According to the Dictionary, the place was originally known as Caer Wrgorn but afterward the town-site was called Lanilltydvawr. In modern times its name is Llantwit Major. The college is gone, but many churches in Wales remain. There was also another famous center of ancient learning at Bangor in the northern region of Wales. More than a dozen regional centers of learning existed in that nation’s history afterward.23“The Liber Landavensis, for instance, bears witness to the existence of many monastic churches in South Wales; … Llancarfan; … Llantwit Major; … Llandough, near Cardiff; … Caerwent, Moccas, Garway, Welsh Bicknor, Llandogo and Dewchurch … and, if as is most likely, ‘princeps’ was but an alternative title, Bishopston in Gower and Penally may be added to the list. […] Nor was the case different in North Wales. In 1147 there was an abbot of Towyn in Meirionydd, while in 856 the death is recorded of a ‘princeps’ of Abergele. Llandinam had its abbot in the middle of the twelfth century, and as late as the fifteenth the memory survived of the abbot and ‘claswyr’ of Llanynys.”

in: Sir John Edward Lloyd, A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, Vol. 1, p. 206.

There was an attempt, spearheaded by Augustine of Canterbury,24by some called: Austin to convene together the leaders of all churches found in Wales with the recently created Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical order, in the early 7th century, around the year 603. The effort was never realized as the Welsh (known as Britons or Cymry) chose not to cooperate with him. So the country of Wales was left to its own devices during an entire period of history, until the reign of William I, who established three lieutenants in the area as Earls. These English lords began to bring Wales under control of the crown. The English king Edward I finally completed this conquest in the year A.D. 1283.

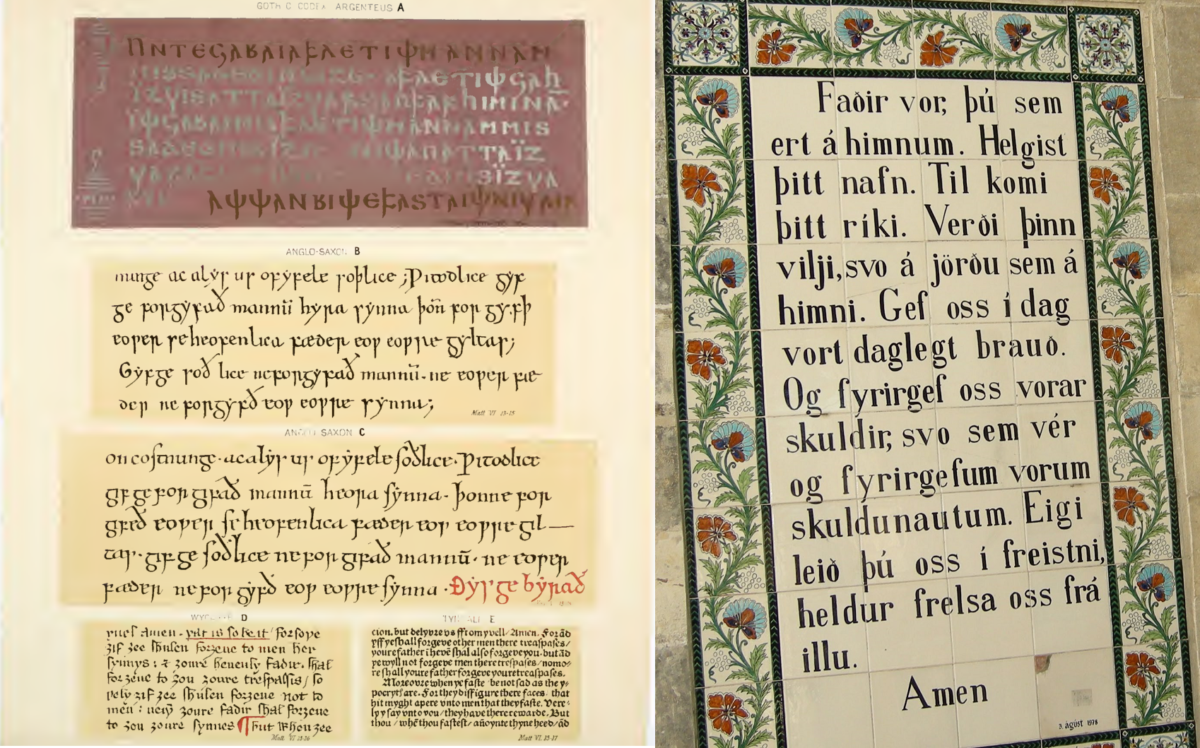

Yet, it was earlier than this year that several known Old English translations of the Bible were produced. Reputedly lost translations date from the first milennium, and well-known commentaries on the Bible, which are not direct translations, date to the Genesis A paraphrase, and also to some ‘glosses,’ written between lines of Latin text, which are found in the Vespasian Psalter and the Lindisfarne Gospels. King Alfred the Great25Ælfred is said to have commissioned translations of several independent passages from the Ten Commandments and from Psalms.26“Ælfred (849-901),” Dictionary of the National Biography (1885-1900), Vol. 1, pp. 158, 161. More directly, it is known that around the year A.D. 990, the turn of the milennium, one translation was commissioned of the four Gospels into Old English.

This translation, Wessex Gospels, on inspection adheres to the received text more than the Vulgate does, as we find later documented by the scholarship behind the Textus Receptus. There is no removal of the last twelve verses of Mark, nor of Luke 17:36, nor of John 7:53-8:11, and Greek forms of Matthew 6:11 and John 3:5 appear intact in the manuscripts of this translation as well.

However despite these developments, study of the classical languages as a discipline undoubtedly suffered during these times. Since literacy remained limited to the upper echelons of educated society, and the written word remained for the most part unmoved from classical languages, it was only accessible to those with education to read, or upon recital. There were many more copies being written than the elements of time could destroy— yet with this, some amounts of transfusion between existing variants, as greater copies were being produced from disparate smaller fragments, and minor typographical errors propagated, so that hybrids were sometimes formed between Vetus Latina and proto-Vulgate texts, or between the original Hebrew and Syriac Old Testament and the Greek Hexaplar Septuagint variants. This was especially true between many minor variants on the Psalms, one of the most popular books of the Bible. Certain variants of Greek manuscripts that omitted sections such as Acts 8:372736 And as they went on their way, they came unto a certain water: and the eunuch said, See, here is water; what doth hinder me to be baptized?

37 And Philip said, If thou believest with all thine heart, thou mayest. And he answered and said, I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God.

38 And he commanded the chariot to stand still: and they went down both into the water, both Philip and the eunuch; and he baptized him.

— Acts 8:36-38 also spread to some extent.

So it is that despite advancements which demonstrate the potential for medieval scholarship to produce translations in Britain, we find by considering that which we have, that work once started in the field of written English translation was left incomplete. This is at least partially attributable to the disposition of those times, but also to the lack of a mechanical copying mechanism, as all manuscripts required a dedicated pen hand to produce. The work of sufficiently copying what already was would have demanded a great amount of labor. But the relative amount of literature that does survive dealing with this subject powerfully demonstrates a continuation of the awareness of the contents of Scripture, rather than a forgetting of Scripture.

The Norman conquest in 1066 brought changes to the ancient English language as ‘Norman French’ was carried across the channel and coexisted as the prestige language in England for centuries. Gradually, from this Middle English emerged.

It is noteworthy to mention that, during the “High” Middle Ages in western Europe (c. 1000-1315), there were also written many independent ‘translation-adaptations’ which attempted to paraphrase the Latin-form scripture, such as the “Anglo-Norman Bible,” a Norman-French paraphrase based on the Latin. It was probably made in the early 13th century and is known by its two surviving copies, one of which contains extensive marginal notes in Middle English to help with the interpretation. This work is known to have originally included all the Scriptural and western Apocryphal books in the traditional order up through Hebrews chapter thirteen.

A more successful translation project resulted in John Wycliffe’s translations, of which about 30 presumed originals still exist (c. 1381-1384), and more than 100 of the later edition (c. 1384-139028edition with John Purvey’s prologue). However, these English translation projects evidently relied heavily on the proto-Vulgate as it existed at the time. So did the earliest mechanically printed Bible, the Gutenberg Bible. This became another iteration of the more regularized Latin Vulgate, as it later influenced the aforementioned Clementine Vulgate (the counter-reformation version of 1592). Gutenberg’s iteration, in turn, was based mostly on the “Paris Bible” (Bible du XIIIe siècle), but with various changes or “emendations” of its own.

However, as we have already seen, the existence of the Wessex Gospels, written about A.D. 990, in Old English, demonstrates a continued presence of the received, classical language form. It clearly says “daily” in Matthew 6:11 and “born” (not “born again”) at John 3:5.

Within about 50 years of Gutenberg’s movable type, the organization of new projects, with the intent to publish standard editions of the Bible for mass production, began in 1502 at the Universitas Complutensis.29when it was located in Alcalá de Henares By 1505 the scholar Desiderius Erasmus had also started to work independently on a similar project, turning down multiple offers to work on the Complutensian project. Both of these projects had the intended aim of placing the best representation of the Latin text in parallel columns with the original language sources. Regardless of the motivations, the end result was that these became the first of many mass-produced, textual-critical editions of the Bible in its original languages, which combined all of the available source manuscripts and high scholarship. The fact that multiple projects were completed independently of each other, and that we can make a comparison of their editions, reveals the level of commonality achieved during the ensuing period.

As we will see, these projects took on increasing levels of sophistication.

By 1514, the Universitas Complutensis had completed and printed its polyglot of the New Testament. However, it would delay the publication of this until the entire project, New Testament and Old, was complete. Three years later, their Old Testament parallel30comprising the first four volumes of the completed work was cleared for release. This interlinear of the whole Bible also included the Hexaplar Septuagint in addition to the Latin and the original-language columns.

However, in the meantime, Erasmus had already published his first edition of the combined New Testament in 1516, called Novum Instrumentum omne. This is now known as “Textus Receptus” via the words taken from one of the last major editions, written over a century later: the Elzevir 2nd edition T.R., which in its preface stated, “the text which you hold, is now received by all: in which [is] nothing corrupt.”31Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum: in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus.

Erasmus would continue his project, releasing five major editions. The third of these, Novum Testamentum omne (1522) became an important source for the English translation project of William Tyndale which began in 1524. The fourth edition of Erasmus was released mainly due to his comparisons with the Complutensian over the book of Revelation, and his inclusion of an additional column showing his own Latin version aside the Vulgate. The Greek column of his fifth edition had as few as four differences from its predecessor, while also dropping the Vulgate column.

It is remarkable that, among the differences between Textus Receptus editions, as well as between the manuscripts themselves, the most frequent are differences of a nature which bear no effect on the translation. This includes variations in spelling of words with more than one spelling,32e.g. the inclusion of the movable nu or variants resulting in equivalent sentences, due to the nature of Koine Greek. We will see later that this minor orthographic variation also specially applies to the so-called nomina sacra found in some manuscripts. The great majority of all textual differences, strictly speaking, fall into this category. Whichever variant or spelling you might take, the translation would be unchanged, because these variations are just a different spelling of the same word, or similar such minor differences that mean exactly the same thing in Koine Greek. There are a few of these that do affect meaning, however, which we will very briefly mention later.

Beginning in 1546, an official royal printer in Paris named Robert Estienne, or Robert Stephens (Latin: Stephanus) began to publish works of the same ambition. He sought to represent the original Greek language New Testament using movable type. Boasting a long career as a lexicographer who had already published the landmark Latin lexicon “Thesaurus linguae latinae,” he went on to produce four editions of the Textus Receptus. In contrast to common assumptions, Stephanus did not attribute any of Erasmus’ editions as a source for his work, instead building his own four editions from an increasing library of Greek manuscripts available to him, the first three increasing in sophistication, and culminating in his 3rd edition ‘T.R.’ of 1550, which afterward became used as a primary source for many scholars in both translation and textual critical studies. His final edition came the next year, with the addition of verse divisions which have become standard in all New Testaments, including the New Testament of the Geneva Bible completed in 1557.

The prominent Biblical scholar Theodore Beza, who in 1558 became resident at Geneva, had at that point already begun his work in the field, having released his own first edition of the T.R. in 1556. At Geneva, Beza would go on to fill the position of primary lector at the academy there, succeeding John Calvin in 1564. He is traditionally ascribed five editions of his own, though with the inclusion of every release he is known to have made, his total work comprises ten editions, of which his most sophisticated and oft cited is his fifth major edition, and ninth overall, published in 1598.

Contrary to public imaginings, these were not all carbon copies of Erasmus’ hastily assembled version of the Greek New Testament, which was more of an aside to his Latin presentation according to his own words. Yet despite this, Erasmus did arrive very closely to the received text purely by nature of the task which he had assigned himself. But through the work of multiple projects by other scholars, of increasing sophistication, time and expense of resources, the limited number of problems with Erasmus’ T.R. editions were thoroughly scrutinized and ironed out of the independent ‘T.R.’ editions of Stephanus, Beza, and later works, all of which conform incredibly closely to one exact version of the scripture. A close examination of Mill’s apparatus, which he collated near the end of his life in 1707, shows the incredible level of uniformity between the editions of later scholars who contributed to the Textus Receptus problem set by collating the differences between authors, of which the vast majority are of no effect on any resultant translation. This demonstrates that the task of textual criticism had been accomplished. The foundation for any future work, it has been shown, had been faithfully laid down, at the appointed time.

Before we move on from the T.R., a comprehensive look at the substantive differences elicited by Mill, and of later collators such as F.H.A. Scrivener, reveals the perceptions of that time as wholly focused on variant Greek readings in a highly limited number of locations that today stand, with perhaps one exception, as well supported by the state of the manuscript evidence today, even if one entirely discounts the evidence of the textus receptus scholars themselves. Variations stand in the following locations:

Luke 17:36

Stephanus (1st thru 3rd ed only): [omit verse]

Beza: include entire verse*

John 16:33

Stephanus: ἔχετε = “have” tribulation

Beza: ἕξετε = “shall have” tribulation*

Romans 12:11

Stephanus: καιρω = “time”

Beza: κυριω = “Lord”*

1 Timothy 1:4

Stephanus: οικονομιαν = “dispensation”

Beza: οικοδομιαν = “edification/edifying/building”*

Hebrews 9:1

Stephanus: σκηνη = “tabernacle”

Beza: [omit word]*

James 2:18

Stephanus: εκ = “by”

Beza: χωρις = “without”*

1 John 2:23

Stephanus: [omit]

Beza: ο ομολογων τον υιον και τον πατερα εχει = “[but] he that acknowledgeth the Son hath the Father also.”*

Indicated with an asterisk are the readings that ultimately became part of the English translations. In every case, the T.R. of Elzevir, 1624 ed., also agreed with Beza, except in Hebrews 9:1 and James 2:18. It is also worth noting that the difference in the book of Revelation 16:5 amounts to Beza’s expansion of a nomen sacrum, so it does not amount to a translational difference as nomina sacra are always expanded into their original form in the translation. Interestingly, Elzevir of 1624 followed Stephanus on this, while the Elzevir (1633) edition concurs with Beza. The final case to touch upon is the one substantive variant found in the Authorized Version (KJV) that is in neither T.R. of Stephanus or Beza. This is the case of John 8:6.

The Authorized Version reads: “This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not.”

The last six words are based on the known source text: “μὴ προσποιούμενος”

The later T.R. did not include these words here at all, but interestingly, the 1516 first edition of Erasmus, the Complutensian Polyglot, and perhaps importantly, the Nuremberg Polyglot did include them. The Nuremberg Polyglot of 1599 is a twelve-language interlinear, including Elias Hutter, the publisher’s, own translation of the New Testament into Hebrew. The Greek column contained this form of John 8:6, which is found in the King James Version.

With regard to these standing locations: with a few exceptions, all of these had been included as early as the Geneva Bible of 1560 and the Bishop’s Bible of 1568, two independent English translations of the Bible, long before 1611. The only exceptions are that in James 2:18, the Bishop’s Bible alone followed Stephanus; and in 1 John 2:23, the Geneva Bible omitted, while the Bishop’s Bible included with brackets.

The King James Bible for its part, included the last six words of John 8:6 and the last part of 1 John 2:23 in italics. This can be seen in the latter case because the word “but” would have been in italics already, so it was placed (since the 1769 edition) in brackets as well to signify double-italics.

In light of this, it is also worth noting emphatically that none of these projects disagreed on their steadfast inclusion of the last twelve verses of Mark, of Acts 8:37, of 1 John 5:7, and of the respective received versions of verses 21:24 and 22:19 in the book of Revelation. The evidence shows that had Beza, Stephanus, Elzevir or the A.V. translators seen any reason to deviate here, or even add a condition, any one of them would not have hesitated to do so. We have to conclude in light of this that they had at their disposal manuscript evidence that we are not considering today, perhaps manuscripts that are no longer available. This should come as no surprise, considering that we rely on many copyists of former times (many of whom we know not their names) having access to former reliable copies of scripture in their respective time. So it makes equally as much sense to say so then, as to say so here. They held these verses in the original Greek, to be the received version of Scripture: the word that all Bibles have ever contained. They agree in unison to throw out the eclectic text variants of modern times, such as the removal of 1 John 5:7. These are the verses that they held up. Considering their superior historical provenance, the conditions under which it so happens they independently worked, their sources’ unfalsifiably preserved existence until this day, and how tightly their independent works, which we have just proven to be independent, conform to one another, it follows that the legitimate study of textual criticism in the original language will be forever limited to at most whatever margin of difference between these witnesses exists. Anything else is equivalent to denial of the doctrine of preservation of the scripture.33Psalm 119:160, Isaiah 59:21, Isaiah 40:8, Matthew 24:35, Luke 16:17, 1 Peter 1:23-25.

It so happens that legitimate textual criticism has since strengthened the inclusion of Luke 17:36 and of the second part of 1 John 2:23. Considering the axioms on which the study of preserved scripture rests, additional manuscript evidence is only able to strengthen existing conclusions, never the other way around. Logically speaking, one can always wait to see more evidence that the received text is right, and has no reason to be concerned with anything that suggests the world has experienced a contra-scriptural history. This is also true, by definition, of anything stated in the word of God. But it seems important to start with the immutability of that word itself, as we have so far done. It seems to have been important to the enemies of that word to start by attempting, by whatever angles and avenues seem available, and in whatever small ways it can manage, to attack this immutability. This is often done by feigning to be a textual critic. When presented with the above, and no longer able to rely on an assumed ignorance of them, it has seemed important to them always to resort to whatever is the next best thing that can be thought of to try to attack its immutability— which is usually, by simply claiming to be a textual critic and scholar that dissents from the above facts, but without providing any justification except that which ignores the above facts.

Now we may close this first part and begin to examine the early English translations of the aforementioned T.R., beginning with William Tyndale in 1524. Again, contrary to common misconception, these translations were not written in Old English or Middle English, but rather they form much of the basis for modern English, as would eventually become formalized in later English literature. The lack of press glyphs such as “þ” at this time would ultimately result in them being dropped from the English language, in this case being replaced with the digraph “th.” This outline will now cover the approach of the Bible to standard English.

Part 2: Timeline of the Bible in early modern English

Within a year of Tyndale’s translation project, he was able to first release an initial draft, in 1525, of his New Testament in English. However, this was interrupted, prompting Tyndale to move his printing activity from Cologne to Worms. He completed the New Testament here in the year 1526, and soon after, these translations were being printed in Antwerp, with the intention of smuggling in the finished work to the people of England. The main virtue of his translations were their low production cost and mechanical consistency, as well as the fact that they were translations based on the received Greek language textus receptus. Great amounts of wealth poured into the project, keeping the print shops running from customers who were interested to obtain a copy.

Also in 1525, a press floor in Venice had begun publication of Daniel Bomberg’s standardized Hebrew-language Old Testament, which he had compiled and edited along with his chief editor, Yaakov ben Hayyim ibn Adonijah (aka ‘Jacob Ben Chajim’). This would serve as an important textual reference for many Old Testaments in Europe until Rudolf Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica in 1906, which became the preferred reference for modern translations. However, the Bomberg 1525 edition was not the only resource available, as the Complutensian Polyglot had for instance included a Hebrew Old Testament in 1517.

By 1530, William Tyndale had completed his own translation of the Hebrew-language Pentateuch into English to go along with the New Testament. In 1531, he also separately translated the book of Jonah. In 1534, he began mass-producing the second edition of his Bible, which contained the New Testament and the five books of Moses from the Old Testament. Around this time, he began further translation projects, by producing the translation of Joshua through 2 Chronicles. In 1535, Tyndale was betrayed to the authorities and imprisoned. Ultimately, approximately one third of the words in the Authorized Version overall are derived from Tyndale’s work.

The project was handed down to Miles Coverdale, who in 1535 published the first Coverdale Bible. This first edition consisted of the second edition of the Tyndale Bible, plus Miles Coverdale’s own translation of the remaining books (Joshua through Malachi, plus apocrypha) but these were derived using his Latin and his German skills, not Hebrew; most likely derived from standardized versions that had long been in print by then. Thus, this became the first printed English translation of the full Bible from any source. A second critically edited edition followed in 1537. By 1538, Coverdale was in negotiations with authorities in England to begin printing officially sanctioned Bibles.

In 1537, John Rogers began publication of the Bible called the Matthew Bible, under a pseudonym Thomas Matthew. This translation contained not only Tyndale’s 1534 work, but also what is likely the unpublished translations of Tyndale from the Hebrew, for Joshua through 2 Chronicles. This edition also included the latest revisions Tyndale had made to his translation of Genesis which could also be found in Tyndale’s rare third 1536 edition. Matthew’s Bible was still in demand and being printed as late as 1551.

The Great Bible is the fourth major translation to bring up. Having been given official sanction from Henry VIII, Miles Coverdale was part of this project. This edition took the Matthew Bible as a base text, and with the endorsement of English authorities it added a handful of interpolations from the Vulgate that were not found in any of Tyndale’s editions of the New Testament up to that point. The Psalms in particular, as the state church Psalter, received editorial attention as they were to be a part of the state church liturgy. However, major or permeating changes did not occur as this Bible still mostly reflected its base text. The Great Bible was released in 1539 and by the end of 1541 it had undergone six editions in quick succession.

As formerly discussed, the later T.R. editions of Stephanus in the years 1546-1551 helped to drive further translation projects of many languages from the reformed academy in Geneva. By 1557, a full translation of the Greek New Testament had been produced by the scholarship in Geneva, who made use of all the reference materials they had available to them, such as the original language manuscripts for textual criticism, versions and manuscripts from the Vaudois and other intermediate-language materials of lexicographical use for the translation, and a library of existing English translational and literary works that would have been available to them at that time to provide further context for the translation. With all of this, the complete Geneva Bible of the first edition was released in 1560. This was the first English Bible to derive entirely from the original languages in both Old and New Testament. It was also several other firsts: first to make use of Stephanus’ critical textual basis, it was printed in a format that was easily carried in the hand and sold cheaply, and it used a more readable Roman typeface font. The Geneva Bible also introduced all the traditional verse divisions. In addition to this, it also contained voluminous marginal notes, of a notably provocative and incendiary reformed theological slant. Most particularly, its footnotes were considered as being subversive to royal authority by high authorities in England. Nevertheless, the Bible came to be very widespread.

At this time the legacy of the Great Bible was seen by many English royalist officials as so strongly challenged, that a new translation was needed on their part, in order to maintain the conformity of the state church sanctioned Bible to the highest standards of textual criticism. In other words, they were motivated to keep pace with the Geneva Bible which everyone knew was more accurate. They were aware of the fact that the officially mandated Bible to be read in churches, the Great Bible of 1539/41, was not fully based on the original language sources and was therefore less accurate. They realized that accuracy of translation to the preserved original language version of the Bible was important.

By 1568, English officials had published their own much more accurate translation, the Bishops’ Bible. This had also made use of Greek and Hebrew scholarship to construct an English text in accordance with the universally acknowledged work underlying the Textus Receptus. The work done was on a scale significantly greater than the Great Bible, with the main feature being a reflection of Stephanus’ corrections to Erasmus, as well as the use of Hebrew for the entire Old Testament, just as the Geneva Bible had done. This represents another independent start-to-finish translation project from the original languages, with consideration for the already existing state of the English language at the time. The only exception to this is the apocrypha were not worked on and remained in their former state from the 1539/41 translation.

However, with the Bishops’ Bible, some unusual choices were made. In their new 1568 translation of the Psalms, the Bishop’s Bible translators had reversed (almost) every reference of LORD and God. This is strikingly apparent in verses such as Psalm 46:734“The LORD of hosts is with us; the God of Jacob is our refuge. Selah.”

— Psalm 46:7 KJV

“The God of hoastes is with vs: the Lorde of Iacob is our refuge. Selah.”

— Psalm 46:7 (Bishops’ Bible) or Psalm 91:2.35“I will say of the LORD, He is my refuge and my fortress: my God; in him will I trust.”

— Psalm 91:2 KJV

“I wyll say vnto God, thou art my hope and my fortresse: my Lorde, in whom I wyll trust.”

— Psalm 91:2 (Bishops’ Bible) Despite this, the Psalter in the back retained the Great Bible translations, which did not exhibit this unusual characteristic. Starting with the 1577 edition, all future editions of the Bishops’ Bible remove the newer translation, and the Great Bible’s version of Psalms is reinserted. Also, starting with the second edition in 1572, future editions of the Bishop’s Bible contained more “ecclesiastical” translations in English as compared to the Geneva Bible. Some of these made it into the Authorized Version, such as “bishoprick” in Acts 1:20 as opposed to “charge,” and “presbytery” in 1 Timothy 4:14 instead of “eldership,” and “charity” instead of “love” in many passages.

It wasn’t long before the Geneva Bible was allowed openly in England. Starting in 1576, at the time of the first major revision, editions of the Geneva Bible began to be printed in Britain. The last major edition of the Geneva Bible was the 1599 edition, following which no major changes have been made. It continued to be printed until the outbreak of the English Civil War. This is when the mostly puritan, presbyterian, independent, and nonconformist parliamentarians began to advocate for the Authorized Version, due in part to endorsements by Oliver Cromwell and others such as William Kilburne. A civil war-era plan to add the Geneva’s footnotes into the Authorized Version was cut short by the dissolution of the long parliament by Cromwell’s faction on Dec. 7, 1648.

The second part of our outline closes with the following notes on the making of the King James Bible (KJV). This was the “Authorized” Version. By its printers and commissioners, it was the official translation, as it succeeded what the previous Bibles authorized by the state had been. This 1611 translation of the Bible was also called ‘Authorized’ in comparison to the ‘Revised Version’ (1880) at the start of the history of the modern versions. The informal name King James Bible specifies details of its origin as having been produced in the year 1611, which was during the reign of King James.

The unacceptability of the Bishops’ Bible editions for the puritans and nonconformists of Britain, and the continued unacceptability of the Geneva Bible (primarily for its footnotes) by royalist authorities of England, led to a situation where one Bible was read in non-conforming congregations and in homes, while another was to be read in state churches. This cause eventually found its way to the heir of the English crown, James VI and I. It was agreed upon between the factions and concluded by the king that an even more substantial translation project would be undertaken, with unlimited access to resources and a large gathering of scholars of all the classical languages. The timing of this project would almost coincide with the latest developments on the T.R. problem set, and had the council been called even five years earlier, the result may have been different in those places where Beza’s T.R. was ultimately used; most notably in the eight locations of substance mentioned earlier. Not only was this the most accurate in that respect, but the translation work was also far more sophisticated and well-supplied than any previously had been, being composed of 54 worthy scholars, of which at least 47 took part. They had more time than anyone had before to focus on completing one translation from the source material. This is, as I will show soon, a great advantage for us today. The entire project was completed in two phases, with the first phase breaking the group into six groups, and the second phase allowing time for a ‘General Committee of Review’ to review the entire translation, line by line. The first phase lasted from 1604-1608, and the second phase began in January 1609. By 1611, editions of the Authorized Version were being printed and sold under official auspices.

Now, we turn to the third section of this outline: an outline of the history of the Bible under modern English or “proper” English, beginning in 1611 until today. To understand what this means, we should first distinguish proper English from the many variations of non-standard English that are out there. That which was used to define words in both the Dictionary of the English Language, 1755 by Samuel Johnson and the American Dictionary of the English Language, 1828 by Noah Webster is considered to be the foundation of the English language as we now know it. It so happens that the only Bible that was in use in the English-speaking world in those years was the A.V., so it follows that since both of these dictionaries cite it as authority for the definitions of words, proper English must then, by its own very definition, conform to the Authorized Version. The alternative would be to say that not only was the Bible wrong in one of its translational choices, but so too are the British and American dictionaries which rely on it as an unchallenged authority. If one is questioning the dictionary on the definition of a word, it follows that one is either trying to change the language from its standard to a non-standard form, or to create a new language entirely. This practice may be simply referred to as the attempt to redefine words.

So, in addition to the unparalleled accuracy of the 1611 translation project— which can be commended to its unique access to what we know are received original language and also intermediate resources, and to its untold level of sophistication and amount of resources dedicated to its task— we may also, from the above remarks which also happen to be true, conclude its unique and singular history in the formation of the English language, as well. By this, it may be said that instead of trying to change the usage of the words in the Authorized Version of the Bible, we ought rather to change our usage of these words to be in line with the Authorized Version. This is if we want to understand standard English. Our word definitions derive from it. As an example, a better precision in measuring light gives us a more accurate realization of the meter because the meter is defined scientifically by the speed of light. So also an increased understanding of the Biblical passages in the Authorized Version gives a better understanding of the English words that it uses and defines, because those words are defined as used in the Authorized Version. This also helps at the same time to understand how one translates from those original languages into the “standard” version of our own.

Part 3: Timeline of the Bible in standard English

It follows from this that the history of the English Bibles from this point on consists of the editorial history of the Authorized King James Bible of 1611. We shall not dwell too much here on the particularities of every subsequent edition— this will be a later subject— but will endeavor to outline the major points of editorial historical development surrounding the A.V., heretofore referred to as being written in proper English. This language may be contrasted with the generally less precise vernacular English dialects of the same era, including contemporary English, which at times will be neutrally referred to in the above context as non-standard. See the appendix below for an example of this usage.

In the first seventeen years of the printing of the Authorized Version, the only holder of the royal letters patent was an official known as the royal printer to the King, Robert Barker. With this came official license to print the Bible for sale. He oversaw the publication of the earliest editions of this Bible. Compared to the consistency of today, these, earliest of all, contained disproportionately many typographical errors and clearly unintended misprints. However, by careful consideration of the evidence, an enormous effort was clearly taken in the first six years to spot and correct every misplaced letter or glyph on the printing plates for subsequent runs.

These corrections would have been made in reference to the handwritten master copy, or by noticing and correcting obvious misspellings in the print sheets. The handwritten copy is now believed to have been destroyed in the London fire of 1666. Nevertheless, it was available and as one might expect, it would have been used as a reference for bringing what are clearly minor printing errors, when noticed, fully in line for future editions. These were especially plenteous in the early editions under Barker, and his editions in the opening years may be categorized as: 1611 1st ed., 1611 2nd ed., 1612, 1613, 1616, and 1617 editions.

Looking past unintended misprints however, the 1611 1st edition is still found to be the true base text for all KJV editions, despite its harder to read archaic word spellings and type font. Nothing to the contrary has been found, despite extensive searching.

Using as examples the most noticeable misprints that exist in the first edition help to explain this. They are as follows:

— In Exodus 14:10 the following was accidentally repeated twice:

and the children of Israel lift vp their eyes, and beholde, the Egyptians marched after them, and they were sore afraid:

— In Leviticus 17:14 the phrase “ye shall eat” was mistyped as “ye shall not eat”

— In Ruth 3:15 the phrase “she went” was mistyped as “he went”

— In Ecclesiastes 8:17 the phrase “yet he shall not find it” was omitted

— In Hosea 6:5 the word “hewed” was mistyped as “shewed”

Of these five instances, four of them were corrected in the 1611 2nd ed., and the Ecclesiastes phrase “yet he shall not find it” was restored in the 1629 edition. Of all the misprints, these five stand out the most, mainly because the last four might be difficult to detect without referring to the master copy; nevertheless these were caught and corrected within the end of the year. Usually, the unintended misprints where they existed would invalidate the spelling or grammar of the sentence in a noticeable way and the correct reading could be easily ascertained. For instance, the 2nd edition corrected Matthew 26:34 which had misspelled “night” as “might” and Mark 14:67 which had misspelled “warming” as “warning” in the 1st edition. The 2nd edition removed the extra repeated word “that” in Jeremiah 15:10, and in Matthew 4:25, when it repeated the word “great” twice.

Other among the few of the most noteworthy corrections were neither drastic misprints, nor were they as unusual as the above, but they were found to be noteworthy for the fact that they reinsert a word that was mistakenly left out in a former edition, which would have probably required access to the master copy in order to rectify. Combined with these was an endless wave of minor typographical errors. Unfortunately, due to the demanding process of the earliest years, Robert Barker did not have time to recycle out the older printing sheets. His solution was to make the first two editions match up in each of their page contents, which allowed him to quickly assemble copies that, we find today, contain some pages from either 1st or 2nd 1611 edition. Neither was Barker’s production process free from the unfortunate instances where new misprints cropped up in his later editions. Although the trend was certainly for more corrections to be found than new mistakes arise, the reputation even in those days of the royal printer’s copies was not fantastic. Until 1628, Barker held the monopoly, so the first seventeen years chronicle his efforts to create a consistent representation of the master copy that he had been given using the archaic technology of the time.

By far the most noteworthy misprints of the 2nd edition were in Exodus 9:13, where it misprinted “serve me” as “serve thee” and in Matthew 26:36, where it misprinted “Jesus” as “Judas,” although the latter would have been easy to detect. These were not in the 1st edition. This is known as the “she” Bible because it fixed the misprint in Ruth 3:15 which had written that “he” went into the city in the 1st edition.

The third edition that Barker released came in the year 1612. It is clear that this project branched off at some point from that of correcting the 2nd edition, because of the 28 most noteworthy corrections found there, the 1612 edition only had 13 of them. The difference with this edition is very noticeable, because this edition was smaller and used the Roman typeface font, as opposed to the gothic-style blackletter of the oversized pulpit Bibles that were the 1st and 2nd edition. Not only did this edition include those 13 of the most obvious misprint corrections, it also included a vast multitude of its own corrections that the 1st and 2nd edition had both missed. These range from the straightforward such as correcting “fro” to proper spelling “from” in Genesis 7:4, and correcting “cried loud” to “cried aloud” in 1 Kings 18:28; to interesting catches as “house of the God” to “house of God” in Ezra 4:24 and “reign therefore” to “therefore reign” in Romans 6:12.

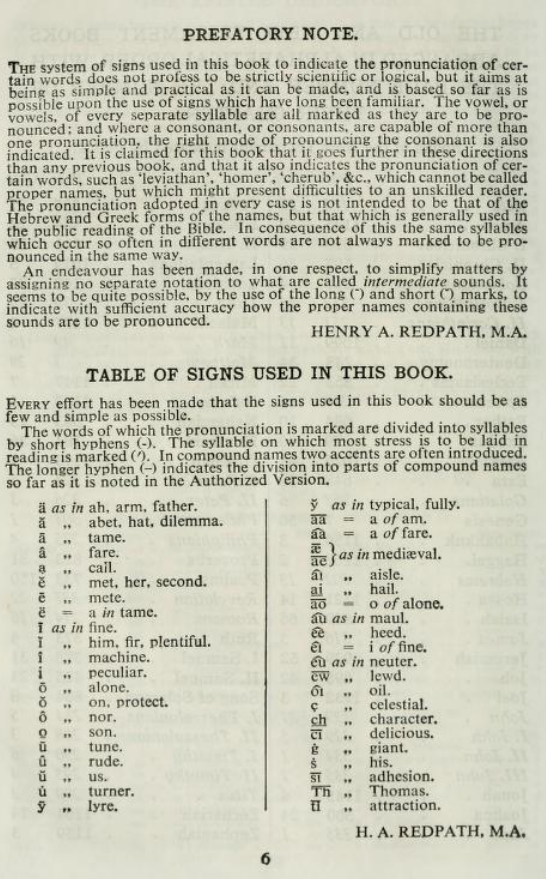

All of these can be seen as clearly unintended misprints being corrected according to a master copy. The relative rarity of substantial misprints (only a tiny fraction of total misprints), the highly consistent translational quality of the text elsewhere, and the relative speed with which the corrections came gives great confidence in this process. Also beginning with the 1612 edition and continuing to the very end of the line, we begin to see another kind of change that is less clearly understood, namely the practice of systematic capitalizations. This may simply have been paid far less attention in the past by the royal printer due to the fact that blackletter capital letters, especially of ‘S,’ are much less visibly different compared to their lowercase. Now that a version was being printed in Roman typeface, it appears an effort was made to bring the text into consistency with itself. It is worthwhile to note, however, that these changes are seen as purely a matter of format, as the words read aloud make absolutely no difference whether capital or lower-case. However, in an effort to convey as much precise meaning as possible, we see that the printers formatted the text as precisely as possible to account for as much minute cross-referential information as could be done.

For this reason, then, it seems that the 1612 edition KJV changed “son of God” in Daniel 3:25 to “Son of God.”36“He answered and said, Lo, I see four men loose, walking in the midst of the fire, and they have no hurt; and the form of the fourth is like the Son of God.”

— Daniel 3:25 Likewise, the word “spirit” was capitalized in 1 Samuel 16:14 (first instance),37“But the Spirit of the LORD departed from Saul, and an evil spirit from the LORD troubled him.”

— 1 Samuel 16:14 and in Romans 8:2, 8:9, 8:11, 8:14, 8:16, Galatians 3:2, 4:6, 5:5, 5:16, 5:17, 5:18, 5:22, 6:8, Ephesians 6:18, Philippians 1:19, Hebrews 10:29, 1 John 4:2, and Revelation 2:11. At the same time the capitalization was removed from “Spirit” in Revelation 17:3.

By 1613 Barker had completed the printing sheets for another blackletter edition, this time in a slightly smaller format than 1611 with more lines per page, thus not allowing him to intersperse pages with the 1611 editions. In this edition the most important corrections from all the previous ones were retained, and more corrections were added.

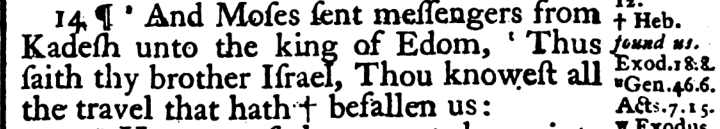

Included in 1613 are the first examples of another interesting kind of correction. Due to the lack of any standardized spelling procedures, as this was before any dictionary had been written, Barker had arranged the word spellings to align each line, substituting ‘&’ and adding extra ‘e’ to the end of words where needed to make the line breaks as manageable as possible. He even used different spellings of the same word mere sentences apart: for example in the 1st edition, the word “flower” was alternatively spelled as “floure” and as “flowre” in James 1:10-11. This lack of any standard spelling of words had an interesting effect on certain word-pairs, for example, “be” and “bee” were used interchangeably in Barker’s editions. Context made it clear which word it is, but later, these spellings would be standardized, so that “bee” only occurs when the insect is being spoken of. Similar pairs are “prey-pray,” “born-borne,” and “than-then.” But perhaps among all word pairs, the most inextricable would be “travail-travel.” We find the first such word spelling resolution here with both Isaiah 13:8 and 21:3 being fixed from saying “travelleth” to saying “travaileth.” It is interesting to note that among the very last set of corrections, not until after 1885, would at Numbers 20:14 also update the spelling of the word “travel” to “travail.”

Other examples of first-time corrections we can attribute to the 1613 edition are those of “my lord” to “my Lord” in Exodus 4:10,38“And Moses said unto the LORD, O my Lord, I am not eloquent, neither heretofore, nor since thou hast spoken unto thy servant: but I am slow of speech, and of a slow tongue.”

— Exodus 4:10 of “Lord” to “Lᴏʀᴅ” (small-caps) at Numbers 20:7, and, most stunning, “spirit” to “Spirit” at John 16:13.39“Howbeit when he, the Spirit of truth, is come, he will guide you into all truth: for he shall not speak of himself; but whatsoever he shall hear, that shall he speak: and he will shew you things to come.”

— John 16:13 Also the year 1613. An interesting restoration is the missing word “hand” to Matthew 6:3 where before it had just said “thy right”. Lastly, however, we mention two short-lived misprints originating in 1613 edition, which are at Ezekiel 23:7 which said “delighted” instead of “defiled” and at 2 Timothy 4:16, it said “may be laid” instead of “may not be laid.”

The 1616 edition followed the 1612 edition as another Roman typeface. It made three interesting restorations that would not be obvious unless the printers had recourse to the original sources. In Leviticus 26:40 the phrase “the iniquity of” was restored to “their iniquity and the iniquity of.” In Ephesians 6:24, the final “Amen” was correctly restored to the Bible. This also happens to be removed by textual critics. Also, in 2 Timothy 4:13, the words “and the books” were now correctly included.

The 1617 edition was a blackletter that seems to most closely resemble the 2nd 1611 edition, and somehow it missed out on most of the corrections of 1612 and 1613, but it did include some that the others missed. Most importantly, in Psalm 69:32 it restored “seek good” to “seek God,” and in Malachi 4:2 the edition redeemed the grammar “and shall go” to “and ye shall go.” It is worth noting that basically all of these (of which I note the most interesting) corrections not only would have brought diffuse misprints in Barker’s KJV editions back in line with the handwritten master copy, but also, bring them back into agreement with the Geneva and Bishops’ Bible, which hold a high degree of conformity in most places and provide further indication that these were unintentional misprints, and where they happened to be found, were never meant to be in the final copy.

After this, demand started to come under control and Robert Barker wouldn’t release any further updates until 1629. However, he had lost the monopoly when in 1628, Charles I also granted the rights to print the Bible to Cambridge University, where for accuracy and editorial prowess Barker’s so-called “London” editions were very quickly left behind. They would also sell for close to production price, ruining Barker’s business. In 1629 the Cambridge edition of the KJV, probably well-prepared in advance, was released to the market. Barker would go on to release several more versions after 1629, but their influence is barely felt; disputably his 1630 edition pre-dated Cambridge 1629 in two locations; In Jeremiah 52:1 the singular “one and twenty year” was corrected to “one and twenty years” and in the book of Revelation 17:4, “precious stone” was corrected to “precious stones,” which makes more sense. The biggest downturn for Barker came in 1631 when one of his presses turned out an edition in 1631 which contained the misprint “thou shalt commit adultery” in Exodus 20:14, leaving out the word “not”. He was fined an excessive amount of money and all the copies were destroyed at his loss, so he ended up spending much of his time in prison after that.

Cambridge University, in league with several of the translators, released their 1629 edition. It offered several advantages. It was printed in a neat Roman typeface, and it updated the word spelling so that the letters ‘u’ and ‘v’ were in their normal places. It also began to use the letter ‘J’ where before ‘I’ had been (archaically for the time) used. These were all causes of complaint that buyers had against all of Barker’s editions. The scholars also started introducing apostrophe as a symbol of punctuation, where before, Barker had included none. They also apparently took over the project of amending the marginal notes and of the apparatus of italic words in the text. They had clearly prepared in advance, because it took them only one year to get an edition to market that corrected far more than any of the “London” editions had. For instance, the word “bee” alone was changed to “be” in 1347 places between Genesis 1:14 through book of Revelation 22:11. The only remaining instances of “bee” referred to the animal. They also had no time to include the apocrypha, which was left out of this edition.

Another interesting distinction the scholars made at Cambridge was the fine subject/object distinction of “ye/you.” They found thirteen places from Genesis 18:5 (third instance) to 1 John 2:13 to correct “you” to the more technically correct “ye” and one place in Isaiah 30:11 to do the reverse.

Several particle corrections of importance were: in 2 Samuel 16:8 the phrase “taken to thy mischief” is really “taken in thy mischief,” in 1 Chronicles 11:15 the phrase “the rock of David” was really supposed to be “the rock to David,” and in Mark 14:36 “not that I will” is supposed to be “not what I will.” Most of the remaining improvements are regimental in nature, having to do with exhaustively improving the spelling consistency, while the rest have broad support from the predecessor Geneva and Bishop’s Bibles as very likely having been in the master copy but misprinted by Barker or his team.

Capitalization corrections continued here with Lord → LORD six times, LORD → Lord a single time, Lord → lord six times, and LORD → lord twice in 2 Chron. 13:6, and Zechariah 6:4.

Also spirit → Spirit 36 times, Spirit → spirit 22 times, and God → god once.

Also, before the 1629 Cambridge KJV, there are two spots in which leave a sour note if left unchanged, these are 1 Corinthians 14:23,40“If therefore the whole church be come together into one place, and all speak with tongues, and there come in those that are unlearned, or unbelievers, will they not say that ye are mad?”

— 1 Corinthians 14:23 mistakenly said “into some place” instead of “into one place” and 2 Corinthians 9:4,41“Lest haply if they of Macedonia come with me, and find you unprepared, we (that we say not, ye) should be ashamed in this same confident boasting.”

— 2 Corinthians 9:4 which had “happily” instead of “haply.” The 1629 Cambridge corrects these. Two other stand out corrections are Galatians 3:13, which had “on tree” instead of “on a tree” and finally book of Revelation 18:12, which now spelt “Thine” as “thyine”. Lastly, the words “yet he shall not find it” were restored to Ecclesiastes 8:17.42“Then I beheld all the work of God, that a man cannot find out the work that is done under the sun: because though a man labour to seek it out, yet he shall not find it; yea further; though a wise man think to know it, yet shall he not be able to find it.”

— Ecclesiastes 8:17

The blogwriter has in his possession a fine copy of this edition that was printed in 1637 and can confirm that there are no apocrypha therein.

The quality of presentation improved with a second major edition by Cambridge and its league of A.V. translators, known as the 1638 edition. The Authorized 1638 Cambridge KJV then became the base text for editions to come by other authors – who were mainly interested in publishing their marginal notes and did little to change the text. This status quo would prevail until the year 1755 when Samuel Johnson’s dictionary came out.

The capitalization corrections in the 1638 KJV stand as LORD → Lord two times and that’s it.

There were also exactly two instances of “you” being corrected to “ye.”

However, in at least some copies, “Ænon” was misspelled as “Enon”. It had been rendered as “Ænon” in 1629.

Incredible are the nature of many of the biggest corrections in this edition, which I have noticed specifically that restore words in a manner rather unlike other editions in this series. The specific sections I refer to here are, as follows, (with 1629 → 1638):

Genesis 19:21 — “concerning this thing” → “concerning this thing also”

Exodus 21:32 — “shekels” → “shekels of silver”

Leviticus 26:13 — “reformed by” → “reformed by me by”

1 Kings 9:11 — “that then Solomon” → “that then king Solomon”

2 Kings 11:10 — “the temple” → “the temple of the LORD”

2 Chronicles 28:11 — “wrath of God” → “wrath of the LORD”

Mark 10:18 — “there is no man” → “there is none”

Romans 14:10 — “we shall” → “for we shall”

2 Corinthians 9:5 — “not of covetousness” → “and not as of covetousness”

Jude v. 25 — “now and ever” → “both now and ever”

Revelation 1:4 — “Churches in Asia” → “churches which are in Asia”

Revelation 5:13 — “honour, glory” → “and honour, and glory”

The reason why these caught my attention is because they all moved the A.V. specifically away from the Bishops’ Bible reading and onto or close to the Geneva Bible reading for those verses.

These at least I did notice among the noteworthy updates of this edition. There may be other changes, which I haven’t checked for this quality among the many less substantial changes. Beyond that, there were some restorations of words which the Geneva and Bishops’ Bible both had, including Mark 5:6 where it is restored from “he came” to “he ran,” and Matthew 12:23 which is restored from “is this the son” to “is not this the son.” Also 1 Timothy 1:4 is returned from “edifying” to “godly edifying”— just as the Bishops’ and Geneva before had.

Needed grammatical corrections followed as well: 1 Corinthians 14:10 was corrected from “are without signification” to “is without signification” and Hebrews 11:23 was corrected from “and they not afraid” to “and they were not afraid”.

Two places are of interest that correct word particles, which are Ezekiel 5:1, which returned from “take the balances” to “take thee balances” and also Daniel 12:13 which returned from “stand in the lot” to “stand in thy lot”. Also, the word “Saphir” updated its spelling to “sapphire” in Lamentations 4:7, in Ezekiel 28:13 and in Revelation 21:19.

After this came many KJV editions that adhered very closely to the Cambridge 1638 edition. They appeared to proceed in three lines. The first line consisted of the 1664 KJV with marginal notes by John Canne, which had a further revision in 1682 that also added an introduction by Canne, and was then used for the 1747 “Scotch” edition. This line appears to have been the first to use spirit → Spirit in Acts 10:19 and 1 Thessalonians 5:19; and Spirit → spirit in Ephesians 1:17. In any case, these three capitalizations ended up in the 1769 revision. The second line consisted of the 1683 KJV which was edited and with marginal notes by Dr. Anthony Scattergood. The most substantial result of the editing here resulted in a greater use of “graduated” punctuation, meaning more colons and semicolons. This seems to have possibly had an influence on the graduated punctuation that was enacted in the 1769 revision. The 1683 KJV was also later used for the “High Anglican” 1701 KJV version by Dr. William Lloyd. It is noteworthy for being the first to include the Ussher chronology tables43albeit as modified somewhat by Lloyd himself in the back of the book, which we may discuss another time. But the 1701 version was not as widely used as they had intended it would be. The third line consists only of the 1743 edition that was made for the SPCK and edited by F.S. Parris. It is known for making a few obvious corrections that fine-tuned the grammar.

Also, by 1675 Oxford University had obtained rights to print the Authorized Version and began selling its slightly different version of the 1638 edition. The “Oxford” editions are easy to identify by their unremarkable variant spellings of specific words. Finally, the royal printers— that is, whoever held the letters patent from London— also began to sell a slightly modified version of the 1638 text, beginning in 1672, which also used slightly different spelling conventions. These are known as the “London” editions.

After a run of Bibles in 1683, the Cambridge side fell silent for about sixty years. Among other things, the publication in 1755 of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language would cause a partnership to be formed for updating the 1638 text, between the printer Joseph Bentham, the bookseller Benjamin Dod, and the editor Dr. Thomas Paris in 1760. Also known to have worked on the project is Dr. Henry Therond. Both editors were of Cambridge University. This group would be instrumental in preparing what became the 1762 revision of the Authorized Version. This is not however to be confused with the 1769 revision.

Armed with the tools needed to perform a permanent update to the spelling and other orthographic conventions of the A.V., as well as other items of interest, Dr. Paris finished the work in 1762 and had the final products printed in Dod’s warehouse. However, a fire subsequently raged through the warehouse, apparently leaving only a small margin of the product, possibly rendering their project unable to replicate any further copies. In any case, only a small handful of copies survived, some of which survive today, but the project was never published. Therefore it is often known as the Cambridge 1762 draft. It is unmistakeable that one of these copies fell into the hands of another editor by the name of Dr. Benjamin Blayney, who worked for Oxford University. Dr. Blayney would eventually incorporate most of the revisions that we see were made by Dr. Paris and would himself make almost as many additional revisions of his own to this, which became the 1769 Oxford edition KJV.

Starting in the 1762 draft, we notice the following advantages over its basis text, the 1638 format. The use of apostrophes to signify possessives becomes standard throughout, whereas previous forms such as “Asa his” are now rendered “Asa’s”. Spelling standards are implemented, where for instance in 477 places, the word “than” is changed to “then” or the inverse according to English convention. Similar with “rend–rent” and others. The italics are also extensively more amended toward the place where they are today.

The word “you” is changed to “ye” in 136 places, and “ye” is changed to “you” in one place.

lord → Lord once in Judges 6:15, Lord → LORD once in Isaiah 34:16.

spirit → Spirit seven times in the Old Testament, and also in Luke 2:27, 4:1.

Spirit → spirit once in 1 Corinthians 2:12 (second instance)44this, along with a comparison between Proverbs 1:23/Joel 2:28, 29, and Acts 2:17, 18, (i.e. pour out vs. pour out of) might give some context for considering the case of 1 John 5:8 as discussed below…

son → Son once in Daniel 7:13

also, Jesus Christ → Christ Jesus once in Romans 3:24.

The following notable individual cases can also be considered to be improvements on the basis of standardized orthographic convention:

Exodus 21:19— “throughly” → “thoroughly”

1 Kings 6:1— “and fourscore year” → “and eightieth year”

Job 14:9— “sent” → “scent”

Isaiah 23:4— “travel” → “travail”

Jeremiah 15:7— “sith” → “since”

Luke 8:5— “the ways side” → “the way side”

1 Corinthians 13:2— “have no charity” → “have not charity”

2 Corinthians 5:17— “past” → “passed”

Philemon v.9— “such a one” → “such an one”

The following may be made on the basis of precise grammar, verb tense or plurality bases:

2 Samuel 4:4— “his feet, and was” → “his feet. He was”

Isaiah 44:20— “feedeth of ashes” → “feedeth on ashes”

Zechariah 4:2— “which were upon” → “which are upon”

Luke 20:12— “the third” → “a third”

Acts 15:23— “and wrote” → “and they wrote”

Romans 4:12— “but also walk” → “but who also walk”

Romans 4:19— “hundred year” → “hundred years”

Romans 11:28— “your sake” → “your sakes”

2 Corinthians 11:26— “In journeying often” → “In journeyings often”

2 Timothy 1:12— “And I am persuaded” → “And am persuaded”

Revelation 22:2— “of either side” → “on either side”

Finally we take note of two irregularities for later, which first appeared in this edition, and would eventually be reversed over time. We note that the 1762 draft says “and Sheba” instead of “or Sheba” at Joshua 19:2, and that at Jeremiah 34:16 it says “whom he had set” instead of “whom ye had set.”

Next to examine is the 1769 Oxford KJV which, as previously discussed, inherited so many of the same revisions as the 1762 Cambridge draft, that it is safe to say that the 1762 edition formed the base text on which further modifications for the 1769 were made. Whereas the Cambridge draft had originally been printed by Bentham at Cambridge, the Oxford KJV of 1769 was printed by Clarendon Press, at Oxford.

Below is a report by Dr. Blayney about this Bible in 1769:

“The Editor of the two editions of the Bible lately printed at the Clarendon Press thinks it his duty, now that he has completed the whole in a course of between three and four years’ close application, to make his report to the Delegates of the manner in which that work has been executed; and hopes for their approbation. In the first place, according to the instructions he received, the folio edition of 1611, that of 1701, published under the direction of Bishop Lloyd, and two Cambridge editions of a late date, one in quarto, the other in octavo, have been carefully collated, whereby many errors that were found in former editions have been corrected, and the text reformed to such a standard of purity, as, it is presumed, is not to be met with in any other edition hitherto extant.

“The punctuation has been carefully attended to, not only with a view to preserve the true sense, but also to uniformity, as far as was possible. Frequent recourse has been had to the Hebrew and Greek Originals; and as on other occasions, so with a special regard to the words not expressed in the Original Language, but which our Translators have thought fit to insert in Italics, in order to make out the sense after the English idiom, or to preserve the connexion. And though Dr Paris made large corrections in this particular in an edition published at Cambridge, there still remained many necessary alterations, which escaped the Doctor’s notice; in making which the Editor chose not to rely on his own judgment singly, but submitted them all to the previous examination of the Select Committee, and particularly of the Principal of Hertford College, and Mr Professor Wheeler.”

It is often stated that the King James Bible that is in use today is that of the 1769 revision, and while this is true on some level, the fact remains that the physical format of the 1769 Oxford edition did still contain some differences significant enough to mention for our study. As with the 1611 edition to this point, none of the changes amounted to a real difference in the translation itself, as it may be read aloud; except where obvious typographical errors were discovered by the producers of the text, which caused it to misalign with the original handwritten translation. In the early days of the Barker editions, through 1629, most of the obvious misspellings were quickly eliminated. But some of the more pernicious typographical errors, ones disguised as legitimate words or almost-correct grammar, lay hidden for longer as the easier ones were removed more quickly. As the proofreading technology and orthographic standards improved, these inaccuracies— whether of a minute technical typographical nature, or of a failure to precisely conform to the original language source in a “difficult to see” way— were corrected: Either way these can all be attributed to some misprint at some stage causing a temporary misalignment to exist. At the same time, many ambiguities of not having standard spellings for words were resolved by the development of these standards. Many times, what originally had been an accepted spelling became technically incorrect, so the spelling was later fixed to account for this. Finally, the format and quality of the apparatuses provided with the Bible only became clearer and more consistent over time. But there could only be so many imprecisions left to find at the end of all of this, and then no more would remain. And, many times, the revisions were purely orthographic, as in the case of capitalizations. It is with this in mind that we continue to proofread the path forward from the 1769 Oxford edition to now.

The 1769 has few capitalization changes aside from the 1762. They include:

God → god once in Acts 28:6

LORD → Lord 4 times: Genesis 30:30, Jeremiah 7:14 (2nd and 3rd), Acts 2:34

Spirit → spirit once in Matthew 4:1

spirit → Spirit twice, in Acts 11:12 and 1 John 5:8

It so happens that all of these, but the first, will be reversed in future editions, so Dr. Blayney’s changes here, did not end up in KJVs of the 20th century, except where he changed “God” to “god” in Acts 28:6.

In the 1769 edition, the word “you” is changed to “ye” in 59 further places, and “ye” is changed to “you” in 11 places.

Starting with the original 1769 edition, the following words no longer share the same spelling but are always used in one correct way: “besides–beside,” “wife’s–wives,” “lifted–lift.”

The following notable individual cases can also be considered to be improvements on the basis of standardized orthographic convention:

Deuteronomy 11:30— “champion” → “champaign”

1 Kings 16:23— “thirty and one year” → “thirty and first year”

2 Kings 11:18— “throughly” → “thoroughly”

Ezekiel 1:17— “returned” → “turned”

Ephesians 2:11— “passed” → “past”

The following may be made on the basis of precise grammar, verb tense or plurality bases:

Leviticus 11:10— “not fins nor scales” → “not fins and scales”

2 Chronicles 16:6— “was a building” → “was building”

Psalm 141:9— “snare” → “snares”

Luke 23:32— “two other malefactors” → “two other, malefactors,”

John 11:34— “they say unto him” → “they said unto him”

Acts 19:19— “many also of them” → “many of them also”

Titus 2:13

— “the great God, and our Saviour” → “the great God and our Saviour”

This essentially concludes all of the most important differences in format that Dr. Blayney introduced, of that which ended up being permanent. What’s listed above was part of the original print 1769 edition printed by Clarendon press in Oxford, and also made it through subsequent editions until today.